We invite you to read through Michael Allsen’s program notes for the May 1st-3rd performance of Voices Eternal.

Program Notes

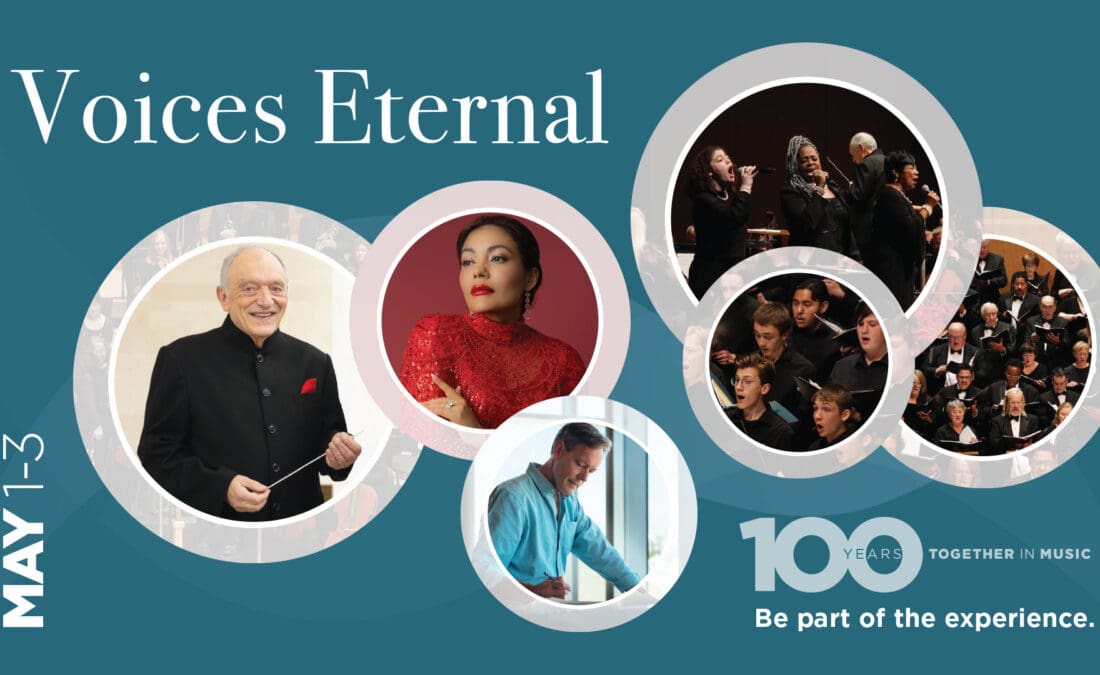

The regular programs of our 100th season close with a large-scale choral/symphonic work commissioned for this occasion. It was written by one of America’s leading composers, Jake Heggie, on a libretto by the distinguished lyricist Gene Scheer. EARTH: A Choral Symphony was specifically designed to include the Madison Symphony Chorus, and our frequent local partners, the Mt. Zion Gospel Choir and Madison Youth Choirs. We also welcome the fine soprano Ailyn Pérez. And to open, we have the most familiar of Beethoven symphonies, the great Symphony No. 5.

The best-known of Beethoven’s orchestral works is the stunning fifth symphony. Beginning with the unforgettable four-note motive that dominates the first movement, Beethoven continuously develops his musical ideas through a lyrical slow movement, a fierce scherzo, and a triumphant finale.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born: December 17, 1770 (baptism date), Bonn, Germany.

Died: March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria.

Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

- Composed: Between 1804 and 1808.

- Premiere: December 22, 1808, at the Theatre an der Wein in Vienna.

- Duration: 34:00.

“It is merely astonishing and grandiose.”

– Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Background

Beethoven’s fifth symphony was a product of his extremely productive “heroic decade” (1802-1812).

Although preliminary sketches of Beethoven’s Symphony No.5 date from as early as 1804, the bulk of the work was written in 1807-08, at roughly the same time as the Symphony No.6. Both symphonies were performed for the first time at a benefit concert in Vienna on December 22, 1808. The program for this landmark (and marathon) event also included excerpts from his Mass in C and the concert aria Ah, perfido, together with premieres of two works with Beethoven himself at the piano, the Piano Concerto No.4 and the hastily composed Choral Fantasy. After a bit of initial resistance from audiences and his fellow musicians—this was, after all, a truly avant garde work—the Symphony No.5 was recognized as a masterpiece and has remained the single most familiar of Beethoven’s works since then.

This was a remarkable work for its time…or any time. Though not as long as his equally groundbreaking “Eroica” symphony of 1803, this work is played by an expanded orchestra that includes instruments seldom heard in earlier symphonies: piccolo, contrabassoon, and trombones. Beethoven was obviously proud of this innovation and wrote to Count Franz von Oppersdorf that “…this combination of instruments will make more noise, and what is more, a more pleasing noise than six kettledrums!” Also new is the degree to which all four movements are linked thematically. The famous four-note motive of the opening movement reappears in all three successive movements, and nearly all of the main musical ideas are linked in some way.

What You’ll Hear

The symphony is in four movements:

• A first movement in sonata form featuring intense development of the

opening motive.

• A lyrical theme and variations.

• A blustery scherzo that ends with with a long transition into the finale.

• A magnificent fourth movement in sonata form, with a titanic coda.

There is no more recognizable motive in Western music than the opening four notes of the first movement (Allegro con brio). Whether or not Beethoven attached a specific meaning to this motto is unclear. His first biographer, Anton Schindler reported that Beethoven referred to this motive as “Fate knocking at the door,” but this may be apocryphal. Later times have attached all sorts of meanings it. For example, during World War II, because of its identity with the Morse Code “V,” it became the musical emblem of Allied victory. At the same time, it was viewed as one of the most purely “German” nationalistic works by the Nazis. In purely musical terms, however, Beethoven’s use of this rhythm in the opening movement is a stroke of genius. With two statements of this four-note motto, Beethoven brusquely tosses aside the stately Classical tradition of long, slow introductions, and jumps directly into the body of the movement (Allegro con brio). The opening theme is almost entirely spun out from the motto, and even the second theme, stated sweetly by the strings, is brazenly announced by the motto from the horns. The motto is also the focus of the development section, which includes some stunning antiphonal effects. The headlong rush of the recapitulation is abruptly broken by a brief oboe cadenza, seemingly at odds with the nature of this movement, but actually a logical continuation of the main theme. Beethoven reserves his most savage fury for the coda, the longest single section of this movement, and another section of intense development.

The second movement (Andante con moto) is a very freely constructed theme and variations. The theme is laid out first by violas and cellos and then more robustly by full orchestra. After three imaginative variations, Beethoven launches into a section of very free development, beginning with a lovely pastoral passage from the woodwinds.

The scherzo (Allegro) begins mysteriously in the low strings but soon picks up as much power as the opening movement, with a statement of the motto by the horns. The central trio moves from minor to major and has a blustering theme in the lower strings developed in fugal style. When the main idea returns, it is strangely muted, and it quickly becomes apparent that this movement is not going to end in any conventional way. In place of a coda, there is a long and mysterious interlude, building gradually towards the most glorious moment in this work: the triumphant C Major chords that begin the finale.

The fourth movement (Allegro) is where Beethoven suddenly augments the orchestra with trombones and contrabassoon. This orchestral effect, probably inspired by contemporary opera, is stunning. The opening group of themes, stated by full orchestra, is noble and forceful and the second group, played by strings and woodwinds is more lyrical, but no less powerful. The development focuses on the second group of themes, expanding this material enormously. Just as the development section seems to be finished, there is a reminiscence of the scherzo—bewildering at first, but then perfectly logical as it repeats the movement’s transitional passage and leads to the return of the main theme. While the recapitulation is rather conventionally laid out, the vast coda continues to break new ground. As in the development section, things seem to be winding to close when Beethoven takes an unexpected turn: in this case a quickening of tempo to end the symphony in a mood of grand jubilation.

The Last Word Goes to Berlioz

According to an account by Hector Berlioz, he brought his former teacher Jean-François Le Seur to an early performance of the Symphony No.5 in Paris. After the final bars, the old man was so excited by the piece that his head was reeling, and he wryly complained that: “One should not be permitted to write such music.” Berlioz replied: “Calm yourself—it will not be done often.”

PLEASE NOTE: Program Notes on the Jake Heggie/Gene Scheer EARTH: A Choral Symphony will be posted later in the season. – JMA

program notes ©2025 by J. Michael Allsen

To view current and past program notes, please visit Michael Allsen’s website.