We invite you to read through Michael Allsen’s program notes for the February 20th-22nd performance of Playful Pursuits.

Program Notes

Guest conductor Tania Miller leads this program, titled “Playful Pursuits.” It opens with a decidedly playful overture by a very youthful Felix Mendelssohn. His A Midsummer Night s Dream captures the dancing fairies and other mischief of Shakespeare’s great comedy. Rachel Barton Pine, who was last with us in 2019, playing the Khachaturian Violin Concerto, makes a welcome return to Overture Hall, this time playing the Korngold Violin Concerto—a romantic, virtuoso work, crafted from several of the composer’s movie themes. Claude Debussy’s Impressionist masterpiece, Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, captures the fleeting, lazy, and occasionally R-rated daydreams of the title character. We close with one of the great ballet scores of Igor Stravinsky, his groundbreaking ballet score Petrushka. Here the title character is a tragic figure, one of three puppets brought to life by a magician.

When he was only 17 years old, Felix Mendelssohn “dreamed” this lively overture, inspired by one of Shakespeare’s greatest comedies.

Felix Mendelssohn

Born: February 3, 1809, Hamburg, Germany.

Died: November 4, 1847, Leipzig, Germany.

Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Op. 21

- Composed: Mendelssohn composed this work in 1826, when he was still a teenager.

- Premiere: The overture was first performed in the Prussian city of Stettin in October 1827.

- Previous MSO Performance: 1944, 1973, 1977, and 2004.

- Duration: 13:00.

Background

Mendelssohn came by his fascination with A Midsummer Night’s Dream naturally: German romantics of the 19th century loved Shakespeare.

No playwright was as beloved by the romantics as Shakespeare: the intense character development and free dramatic form of Shakespeare’s works was a source of inspiration for dozens of composers. The Bard’s popularity was wildest in Germany, where his works were known through a translation published by August von Schlegel and Ludwig Tieck in 1801. (There is an old German witticism to the effect that: “Shakespeare is best read in the original German.”) The 17-year-old Mendelssohn and his sister Fanny spent the summer of 1826 in the garden of their family’s home in Berlin, reading Shakespeare. Mendelssohn was impressed enough by his first reading of Ein Sommernachtstraum that he decided almost immediately to write a piece that captured the play’s spirit. In early July he wrote to a friend: “I have grown accustomed to composing in our garden. Today or tomorrow, I am going to dream there A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream. This is, however, an enormous audacity…” Audacious or not, he wrote the overture in just a few weeks—some of his most delightful and overtly programmatic music. He dedicated the Overture to the Prince of Prussia, and seventeen years later, at the request of the prince—by then King of Prussia—Mendelssohn provided several additional pieces of incidental music for the play. The incidental music, though written by a much more mature composer, perfectly matches the youthful vitality of the Overture.

What You’ll Hear

Though it is set in a relatively conventional Sonata form, it is easy to hear Shakespeare’s plot in this work.

The Overture begins with a series of almost hesitant chords, as if fairies are shyly peeking around trees. The fairies themselves appear in a light string passage before the full orchestra enters joyfully, in a passage that sounds distinctly like the much later Wedding March. There are the horns of Duke Theseus’s party, and a flowing Romantic theme for the various pairs of lovers, and finally a rustic dance, in which you can clearly hear the “hee-haws” representing the irrepressible Nick Bottom. The development focuses on the opening fairy music, becoming almost melancholy at the end before the familiar chords bring in a varied recapitulation of the main themes. The overture closes with a reverent version of the wedding music and a final statement of the mysterious chords. One point of interest in the orchestration is that Mendelssohn wrote a prominent part for a now-obsolete bass instrument, the serpent. When he resurrected the overture in 1842, he substituted the ophicleide. The part is played today on the tuba.

Most of the themes of this grand romantic violin concerto come from Korngold’s movie scores.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Born: May 29, 1897, Brno, Czechoslovakia.

Died: November 29, 1957, Los Angeles, California.

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D Major, Op.35

- Composed: Korngold completed his Violin Concerto in 1946, though most of it is nearly ten years older. The score is dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel, widow of Gustav Mahler, who had been Korngold’s childhood mentor.

- Premiere: February 15, 1947, with violinist Jascha Heifetz and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra.

- Duration: 24:00.

Background

Korngold was part of the wave of musicians who emigrated to the United States in the 1930s, fleeing and increasingly repressive and dangerous Europe-—to the immense benefit of American musical life. Like many of his fellow émigrés, Korngold found work scoring Hollywood films.

Korngold, born in Bohemia but raised in Vienna, began composing as a child. His father, an influential music critic, was able give him access to the greatest musicians in Vienna, but young Korngold was clearly a prodigy, and at age nine, Gustav Mahler hailed him as a genius. Through the 1920s, he maintained a career as both a conductor and as a composer, and his 1920 opera Die tote Stadt (The Dead City”) was particularly successful. By the 1930s, life for a Jewish artist in Austria was becoming increasingly hazardous, and in 1934 he accepted an offer to come to Hollywood to work on a film score. He spent the rest of his life there, and would write nearly two dozen film scores, mostly for the Warner Brothers studio. Korngold’s bold, thoroughly romantic style made him a natural for swashbuckling Errol Flynn adventures like Captain Blood (1935), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), and The Sea Hawk (1940). He returned increasingly to concert music after the war—he had in fact vowed never to write anything but film scores until Hitler was defeated.

In early 2005, I was able to consult with John Waxman, son of Korngold’s Hollywood colleague Franz Waxman, and Kathrin Korngold Hubbard, Korngold’s granddaughter, on the complicated genesis of his most popular concert work, the Violin Concerto. The initial suggestion that Korngold write a violin concerto came from Franz Waxman, and he was at work on the piece in 1937-38. Kathrin Korngold Hubbard notes that in 1938 there was a “tryout” performance by violinist Robert Pollack, a family friend, who was not able to effectively play this difficult piece. Disappointed by the performance, and tied up with work on Robin Hood, Korngold set the score aside. In 1945, with the war over, he set to work again on the concerto, when he began to rewrite it for the virtuoso Bronislaw Huberman. It would not be Huberman who performed it for the first time, however, but Jascha Heifetz. According to John Waxman, this was the result of a dinner party at his father’s Hollywood home that included the Korngolds and Rudolph Polk and his wife. Polk—Heifetz’s manager, and a fine violinist in his own right—asked Korngold why he had never written a violin concerto. The subject was quickly dropped, but later that evening, as the men and women went to separate rooms, Luzi Korngold revealed the story to Mrs. Polk. Polk phoned Korngold the very next day to request the score for Heifetz, and Heifetz himself phoned Korngold the day after that, asking permission to play the work’s premiere. The two worked together on the final version—at Heifetz’s insistence, making the concerto even more difficult! In her biography of Korngold, Luzi Korngold notes that when Huberman visited them afterwards, that the composer told him: “Huberman, I haven’t been unfaithful yet, I’m not engaged…but I have flirted.” Huberman graciously offered to play the concerto after Heifetz’s premiere—but died in 1947 before he could perform it. The world premiere concert in St. Louis in 1947 also included a virtuoso work written for Heifetz by Franz Waxman, the Carmen Fantasy. Regarding the concerto’s premiere, Korngold wrote:

“In spite of its demand for virtuosity in the finale, the work with its many melodic and lyric episodes was contemplated rather for a Caruso of the violin than for a Paganini. It is needless to say how delighted I am to have my concerto performed by Caruso and Paganini in one person: Jascha Heifetz.”

What You’ll Hear

This concerto is set in three movements:

• A broad opening movement in a variant of sonata form.

• A lyrical Andante.

• A fast-paced and sometimes humorous set a variations

Though it was written in the 1930s and 1940s, the Violin Concerto is a work of pure turn-of-the-century Viennese romanticism. It also draws on themes from several of his film scores. The first movement’s (Moderato nobile) contemplative opening theme—heard first in the violin and then in full orchestra—appeared in his 1937 score for Another Dawn. A lighter transition leads to a lyrical second idea, a lush idea that appeared as a love theme in the film Juarez (1939). (It’s possible that in this case, the borrowing went the other direction—that this music may have been borrowed from the then-shelved violin concerto.) After an extended solo cadenza in the middle, the movement ends with a rather free development of the two main ideas. The second movement (Romanze: Andante) continues in the same lyrical style. This movement shares much of its musical raw material with Korngold’s Oscar-winning score to Anthony Adverse (1936). The violin introduces the main theme through a gauzy accompaniment of strings and harp. There are a few more playful moments, but the wistful mood is otherwise constant through this quiet movement. The finale (Allegro assai vivace) is a set of variations on a theme used in his score to The Prince and the Pauper (1937). There is a lot more “Paganini” than “Caruso” in this movement: this is mostly wry and lighthearted music that allows the violin to shine in brilliant technical passages, ending in a humorous coda.

This quiet work was thoroughly revolutionary for its time and secured an international reputation for its composer.

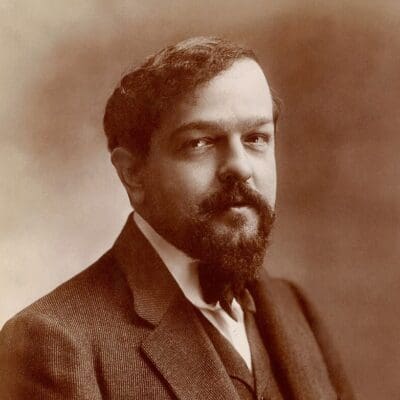

Claude Debussy

Born: August 22, 1862, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France.

Died: March 25, 1918, Paris, France.

Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun

- Composed: 1892-94.

- Premiere: December 22, 1894, in Paris.

- Previous MSO Performance: We have performed the work eight times at these programs between 1938 and 2019.

- Duration: 18:00.

Those nymphs, I want to make them permanent.

So clear, their light flesh-pink, it hovers on the atmosphere

Oppressed by bushy sleeps.

Was it a dream I loved?

– Mallarmé, The Afternoon of a Faun (translated by W. Austin)

Background

This work grew out of Debussy’s fascination with Symbolist poetry. It was originally written for a planned theatrical production of his friend Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem The Afternoon of a Faun.

The composition of the Prélude á l’après-midi d’un faune marked a clear turning-point in the career of Claude Debussy. He had attended the Paris Conservatoire as a young man and in 1884 had won the prestigious Prix du Rome, the stamp of approval from the French musical establishment. In the late 1880s—what he later called his “bohemian years”—he scratched out a living in Paris as an accompanist and composer and absorbed all of the musical influences in the air. In these years he befriended many of the most forward-thinking musicians in Paris, flirted with the music of Wagner (even making two pilgrimages to Bayreuth), and was deeply impressed by a performance of Javanese gamelan music he heard at the Paris Exposition in 1889. One of the most important influences from around 1890 onwards was his association with the Symbolists. Just as Impressionist painters like Monet and Renoir were rejecting realism in favor of pure color and light, the Symbolist poets rejected rigid poetic forms and description in favor of a free and sometimes kaleidoscopic style, in which fleeting images become symbols of deeper truths. Symbolism was the avant garde in French poetry from the 1880s through the turn of the century, and Debussy associated with many of the movement’s leading poets: Verlaine, Baudelaire, Valéry, and Mallarmé. The Symbolists often described their poetry in musical terms—imagery that expresses what cannot be directly expressed in words—and Debussy responded by setting many of their poems as art songs, or, as in the case of his Prelude, using their works as inspiration for purely instrumental compositions. Stéphane Mallarmé was a particularly important contact for Debussy—he hosted weekly salóns at his home, inviting poets, artists, and musicians to present and argue over their latest works. Debussy was a regular at Mallarmé’s salóns in the 1890s, and their association led to the composition of Debussy’s most famous orchestral piece.

It went through several different versions from the 1870s onwards, but Mallarmé’s lengthy poem The Afternoon of a Faun was nearly in its final form in 1890, when he asked Debussy to provide music for a projected theatrical presentation of the work. Mallarmé’s poem is vaguely erotic throughout, with a faun free-associating on his encounters with various nymphs. Debussy’s Prelude, written between 1892 and 1894 was all that ever came of the theatrical presentation, though in 1912, Vaclav Nijinsky choreographed a ballet on Debussy’s Prelude for the Ballets Russe. (Nijinsky’s ballet went far beyond Debussy’s music and even Mallarmé’s poem in its frank sexuality—so much so that it shocked even a Parisian audience!) Debussy’s Prelude was a stunningly avant garde work for 1894, and more than any other piece, made Debussy an internationally known composer. Rather than setting this as a conventionally programmatic symphonic poem, Debussy tried to capture the ambience of Mallarmé’s poetry without really telling a story. Mallarmé, after hearing Debussy play the score on piano for the first time, exclaimed: “I didn’t expect anything like this! The music prolongs the emotion of my poem and sets its scene more vividly than color.” Though critics generally—and predictably—disliked a piece as startlingly new and radical as the Prelude, audiences and musicians took to it quickly and it was being performed across Europe and in the United States within just a few years.

What You’ll Hear

The work’s outer sections are dominated by repeats of the famous opening flute solo, but Debussy develops this idea in a radically unorthodox way.

On the surface, the Prelude has a conventional three-part form: an opening section that is repeated in varied form at the end, and a contrasting middle section. However, there is nothing conventional about the way that Debussy constructed the work. The main idea—perhaps representing the faun himself—is the familiar flute theme heard in the opening bars. Mallarmé jotted a brief poem about this melody on the first page of the manuscript score: “Sylvan of the first breath: if your flute succeeded in hearing all of the light, it would exhale Debussy.” This theme reappears some eight times in the course of the work, but it is never developed in a traditional way. Each time it shows up it ends—like one of the faun’s lazy thoughts—by spiraling off into new, unrelated ideas. The flute theme dominates the two outer sections, and the middle section presents a succession of contrasting ideas. There are a few climactic moments in this central section, but the music is never strident, and the scoring remains transparent and colorful through the whole work. (As apt as the designation “Impressionistic” seems for the music of Debussy, it is worth noting that he disliked the term just as much as the “Impressionist” painters!) The coda presents one final mysterious reference to the faun in the horns, before the music evaporates into silence.

Petrushka—the second of the groundbreaking ballets that Stravinsky wrote for the Ballets Russe—began as an informal exercise in composition designed to “refresh” him prior to beginning work on Rite of Spring.

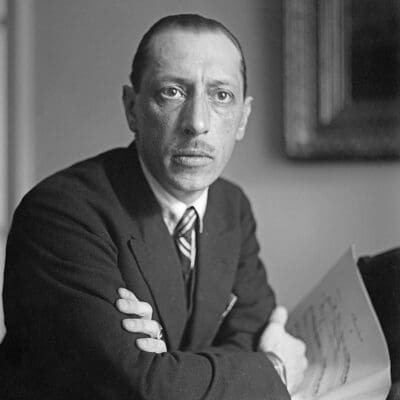

Igor Stravinsky

Born: June 17, 1882, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Died: April 6, 1971, New York City.

Petrushka Suite (1947 version)

- Composed: 1910-11. In 1946, Stravinsky arranged a suite for concert performance and published it in 1947.

- Premiere: It was first performed by the Ballets Russe in Paris, on June 13, 1911.

- Previous MSO Performance: 1971 and 1998.

- Duration: 35:00.

“Only a straw-stuffed puppet, this modern hero!

– Wallace Fowlie

Background

Like its companion works Firebird and Rite of Spring, Petrushka frequently uses Russian folk tunes in its music.

In 1911, the Parisian public expected great things of young Igor Stravinsky. There was an ongoing craze for Russian music and ballet, fueled by the shrewd impresario Serge Diaghilev, who had brought Stravinsky to Paris two years earlier. Stravinsky’s Firebird (1909)—his first ballet score for Diaghilev’s dance company, the Ballets Russe—had been an enormous success, and by 1911, he was already beginning work on the revolutionary score for Rite of Spring. According to his autobiography, his second work for the Ballet Russe, Petrushka, began as a sort of compositional coffee break between Firebird and Rite of Spring:

Before embarking on Rite of Spring, which would be a long and difficult task, I wanted to refresh myself by composing an orchestral piece in which the piano would play the most important part—a sort of Konzertstuck [concert piece]. In composing the music, I had in mind a distinct picture of a puppet, suddenly endowed with life, exasperating the patience of the orchestra with diabolical cascades of arpeggi… Having finished this bizarre piece, I struggled for hours, while walking beside Lake Geneva, to find a title which would express in a word the character of my music and consequently the personality of this creature.

One day, I leapt for joy. I had indeed found my title—Petrushka, the immortal and unhappy hero of every fair… Soon afterwards, Diaghilev came to visit me in Clarens, where I was staying. He was much astonished when, instead of sketches of the Rite, I played him the piece Petrushka. He was so much pleased with it that he would not leave it alone and began persuading me to develop the theme of the puppet’s sufferings and make it into a whole ballet.

Stravinsky’s hero, Petrushka, is one of the stock characters of the puppet shows that were a feature of fairs in Russia. He is a close cousin to Harlequin/Arlecchino of the Commedia dell’Arte—a vulgar, low-class clown—but here he takes on a tragic role. The scenario that Stravinsky and Diaghilev created is set at a Shrovetide fair (Mardi Gras or Carnival in our part of the world) in St. Petersburg, complete with dancing bears, masqueraders, and a puppet show. The puppets—Petrushka, the Ballerina, and the Blackamoor—suddenly come to life. The ballet, which was partly done in pantomime, is a tragic love triangle between these characters, in which Petrushka is killed. At the close of the ballet, the Magician reassures everyone at the fair that Petrushka is merely a puppet, but Petrushka’s ghost appears to mock him. The ballet ends as the Magician flees in terror.

Petrushka was a hit in Paris, and again a year later in England. Diaghilev took the Ballets Russe on an extensive tour of the United States in 1916. Petrushka was the first exposure to Stravinsky’s music for audiences in New York City, Chicago, Milwaukee, Los Angeles, and many other American cities. Though some audience members (and many critics) were bewildered by this “ultramodern” score, Petrushka was generally well-received on this side of the Atlantic. (It’s a sad commentary on our country at this time to note that the music was, in fact, much less controversial in America that the fact that a black character, the Moor, killed the white Petrushka!) The ballet remained in the company’s repertoire until it was disbanded in 1929.

The score was published in 1912, and Petrushka was frequently played as a concert work. However, the fact that the ballet ended with a long, quiet episode, and the expanded orchestra required made it a problematic concert piece. In 1947, Stravinsky published a completely revised concert suite version of Petrushka, setting it for a standard orchestra, clarifying several problematic passages, and re-ordering the original four tableaux into seventeen movements, which are played without pauses. At least part of Stravinsky’s rationale seems to have been simply to renew his copyright on the piece. In any case, the suite works wonderfully as a concert piece.

What You’ll Hear

The 17 interconnected movements of the Petrushka Suite largely follow the plot of the ballet.

The opening and longest movement, The Shrove-tide Fair, shows the whirl of activity at the fair. Stravinsky’s music is based upon at least one, and possibly several Russian folk tunes. The Magician is a sudden break in the excitement as people gather around to see the Magician bring his puppets to life with a flute. This section leads directly to the Russian Dance, as the three puppets dance a wild trepak for the fairgoers. Petrushka shows this miserable puppet in his miserable cell, cursing and mooning over the Ballerina, who eventually pays him a visit, and dances briefly with him, before leaving him alone. The Blackamoor shows Petrushka’s rival lounging in his room, which is elegantly furnished. The Ballerina announces herself with a cornet fanfare and then dances a little mechanical solo for the Moor. The two then dance an insipid Valse together, to a pair of tunes that Stravinsky borrowed from the Viennese waltz composer Joseph Lanner. A jealous Petrushka bursts into the room, and struggles with the Moor briefly, before the Moor tosses him out the door.

At this point in the 1947 suite, Stravinsky brings together a reminiscence of the opening music, Shrove-tide Fair (Towards Evening), and a series of dances drawn from the fourth of the ballet’s tableaux. The Wet Nurses’ Dance is based on two Russian tunes, the first introduced by solo oboe, and the second by oboe, trumpet, and finally full orchestra. Peasant with Bear has the peasant characterized by shrill clarinet, and the bear by solo tuba. Gypsies and a Rake-Vendor has a rather drunken merchant enter with two Romany girls—he tosses banknotes to the crowd and his girlfriends dance seductively. This is followed by a robust Dance of the Coachmen, which is also based on Russian folk material. The suite’s Masqueraders is a wild dance sequence that leads up to Petrushka’s death in the ballet. The music brings together a flurry of images—dancers dressed as a devil, a goat, and a pig taunt the crowd before everyone joins in a frenzied dance. Suddenly, everything stops for The Scuffle, as the enraged Moor, sword drawn, chases Petrushka across the stage and, amidst chaotic music, strikes him dead. The Death of Petrushka presents fragments of Petrushka’s melody above tense string tremolos. In Police and Juggler, an officious policeman—in the guise of a lugubrious bassoon solo—is summoned, but he is apparently satisfied by the Magician’s assurance that these Petrushka was only a puppet. In the final scene, The Vociferation of Petrushka’s Ghost, Petrushka’s ghost appears above the puppet theater (voiced by a pair of shrill muted piccolo trumpets) to taunt and threaten the Magician, who flees in terror.

program notes ©2025 by J. Michael Allsen

To view current and past program notes, please visit Michael Allsen’s website.