We invite you to read through Michael Allsen’s program notes for the June 14th 4:00 pm performance of A Community Gift and Dream — for the Love of Music.

Program Notes

Our season-long centennial celebration closes with a joyous festival concert, which also serves as Maestro DeMain’s final concert as music director. It opens with Shostakovich’s bubbly Festive Overture, which seems to have been a reaction to the death of his persecutor, Josef Stalin. Next we welcome a soloist for whom the Maestro and the musicians of the MSO have great affection, violinist Julian Rhee, who won his first concerto competition with the Madison Symphony Orchestra at age 9(!), and who is launching what will certainly be a stellar career as a soloist. He plays a flashy virtuoso showpiece, the brilliant Carmen Fantasy by Sarasate. Next is a showpiece for the orchestra itself, Gershwin’s lively An American in Paris. The orchestra then turns to a set of evocative pieces from Gustav Holst’s The Planets. Our closer, featuring the Madison Symphony Chorus, is perhaps the greatest musical expression of pure joy, the choral finale of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9.

This relentlessly cheerful little overture was written for a theatrical event in Moscow in 1954…but it also seems to be the composer’s reaction to the death of Josef Stalin!

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Festive Overture

When Josef Stalin died on March 5, 1953, life for Soviet artists began to change, gradually at first, and then with increasing speed, as the tight controls of the 1930s and 1940s relaxed. Shostakovich had suffered under Stalin. After withdrawing his fourth symphony in 1936—at least partly to avoid censure for “modernistic excess” from Stalinist authorities—he redeemed himself in the eyes of the Party with the powerful and bombastic fifth. If the sixth was suspiciously tragic and impudent in tone, he redeemed himself once again with the seventh and eighth symphonies: enormous wartime works that take their cue from events of the Great Patriotic War. With the ninth symphony, composed at the very end of the war in 1945, Shostakovich again found himself suffering Stalin’s displeasure: this boldly sarcastic work had none of the pompous jubilation expected after the great victory. The composer was formerly censured by Soviet musical authorities in 1948, for “formalistic distortions and anti-democratic tendencies alien to the Soviet people.” It is no surprise, then that Shostakovich kept his head down for the next several years: composing easily accessible film scores, and politically safe pieces like the oratorio Song of the Forests.

Shostakovich’s immediate response to Stalin’s death was the tenth symphony, a return to an uncompromising modernist style. The brief Festive Overture, hardly modernist in any way, seems to be a response of a different sort: light and exuberantly happy. Shostakovich had gradually worked his way back into favor with Soviet authorities, and in 1954, he was named to a post with the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. In late 1954, the Bolshoi was chosen to host an important celebration of the 37th anniversary of the 1917 revolution and turned to Shostakovich for a suitably joyful piece to open the festivities. They waited until just a week beforehand to inform him, however! Shostakovich seems to have been unfazed—his friend Lev Lebedinsk recalled how he composed with amazing speed and was able to make jokes at the same time he was writing down music. Lebedinsk also recalled hearing the new piece for the first time: “Two days later the dress rehearsal took place. I hurried down to the Theatre and I heard this brilliant effervescent work, with its vivacious energy spilling over like uncorked champagne.”

The Festive Overture begins—no surprise—with a grand brass fanfare. The tempo abruptly changes to Presto for the main theme, a bubbly clarinet theme that is varied in several ways. The second theme for horn and strings is more flowing and romantic, though an irrepressible accompaniment figure continues the previous sense of energy. This ends in a witty pizzicato idea from the strings, and return of the first Presto music, eventually combined with the second theme, now played by the brasses. A short transition, and then a triumphant return of the fanfare, before Shostakovich ends with a rousing coda.

This virtuoso showpiece elaborates on seductive themes from Bizet’s Carmen.

Pablo de Sarasate (1844-1908)

Carmen Fantasy for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 25

Like our soloist at these concerts, the great Spanish virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate started early. He had his first public recital at age eight, and within two years, the Queen of Spain helped him with a scholarship to the Paris Conservatory. Sarasate won the Conservatory’s first prize at age thirteen, and was then went on to a long and successful career as a touring soloist, appearing in every country in Europe, and travelling widely in North and South America. In an age of extremely flamboyant soloists, Sarasate was widely admired for his subtlety, and several of the leading composers of the late 19th century dedicated works to him. Like many Romantic virtuosos, Sarasate also composed works for himself, including the one heard here.

Most of his original works play on Spanish musical material, but his famous Carmen Fantasy deals with Spanish material by way of a French opera. After an initially unsuccessful run, Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen quickly became one of the most popular and universally beloved operas of the late 19th century. (In true romantic irony, Bizet never saw this success—he died just three months after the premiere.) One sure sign that an opera was popular was the appearance of reworkings of its music by instrumental virtuosos. Sarasate’s Carmen Fantasy is only one of dozens of versions of the opera’s music for various instruments, but it is one of the very few that have endured in today’s solo repertoire as a virtuoso showpiece. Sarasate sets the piece in five short sections, each of which draws on a section of the opera. The opening (Allegro moderato) begins with a smoky version of the Aragonaise that opens Act 4, but quickly expands into in a variety of showy effects. This leads to a version of the Carmen’s famous entrance aria, the sexy Habanera (Moderato), which gets a brilliant variation by Sarasate. The slower middle section (Lento assai) is a version of Carmen’s mocking of the officer Zuniga, which moves to her languorous Seguidilla (Allegro moderato), and then seamlessly into the wild dance of Carmen and her sisters (Moderato) as they entertain the soldiers at the beginning of Act 2. Sarasate uses this dance as the vehicle for some brilliant virtuoso fireworks and he ends with a blazing coda.

Gershwin’s An American in Paris is a musical picture of an American—undoubtedly Gershwin himself—wandering through the City of Lights in the 1920s. Its music is lively and colorfully orchestrated…including those famous taxi horns!

George Gershwin (1898-1937)

An American in Paris

Throughout his all-too-brief career Gershwin lived a kind of double life, with feet planted in both Broadway and in what he considered to be more “serious” Classical music. His first big splash on Broadway was the hit song Swanee in 1919. His big moment in the Classical world came just five years later. Paul Whiteman, the so-called “King of Jazz” announced an “Experiment in Modern Music” for February 12, 1924, a concert that would supposedly answer the question “What is American Music?” Somewhat to his surprise, Gershwin read in the newspaper that he would be composing a “jazz concerto” for Whiteman’s event. With help from Whiteman’s staff arranger, Ferde Grofé, Gershwin completed Rhapsody in Blue in about a month, and played as piano soloist. Whiteman’s pretentious “Experiment” was a partial success, but Rhapsody in Blue was clearly the hit of the show. Within a year, he was approached by Walter Damrosch, conductor of the New York Symphony Society. Damrosch, who had been at the Whiteman concert, gave Gershwin a commission for a “New York Concerto.” The result, the Concerto in F, is a more ambitious piece than the Rhapsody, and has become the most successful of all American piano concertos. In 1928, Damrosch offered a second commission, this time for an orchestral work.

In March 1928, George and Ira Gershwin, together with their sister Frances and Ira’s wife Leonore, left for a European tour, spent mostly in Paris. Paris of the 1920s was the center of the artistic world: host to a dazzling array of composers, artists, jazz musicians, dancers, writers, and poets—both French and foreign. Gershwin, who was still a bit self-conscious about his reputation as a “serious” composer, nevertheless took every opportunity to schmooze the composers he admired most: Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Poulenc, Ravel, and Milhaud. Gershwin brought the unfinished score for the new orchestral piece with him to Europe and sketched out much of the score in Paris that spring. He completed the full score and orchestration by November 1928. Reviews of the first performance were decidedly mixed, but the best answer to the critics was success: An American in Paris became an orchestral standard almost as soon as it was premiered.

Gershwin provided the following outline of the work:

This new piece, really a rhapsodic ballet, is written very freely, and is the most modern music I’ve yet attempted. The opening part will be developed in a typical French style… though the themes are all original. My purpose here is to portray the impression of an American visitor in Paris, as he strolls around the city, and listens to various street-noises and absorbs the French atmosphere. As in my other orchestral compositions, I’ve not endeavored to represent any definite scenes in this music. The rhapsody is programmatic only in a general impressionistic way, so that the individual listener can read into the music such as his imagination pictures for him.

The opening gay section is followed by a rich blues with a strong rhythmic undercurrent. Our American friend, perhaps after strolling into a café and having a couple of drinks, has succumbed to a spasm of homesickness. The harmony here is both more intense and simple than in the preceding pages. This blues rises to a climax, followed by a coda in which the spirit of the music returns to the vivacity and bubbling exuberance of the opening part, with its impressions of Paris. Apparently the homesick American, having left the café and reached the open air, has disowned his spell of the blues, and once again is an alert spectator of Parisian life. At the conclusion, the street noises and French atmosphere are triumphant.”

Gershwin’s use of the orchestra in this work is much more confident than in either the Rhapsody (which, after all was arranged almost entirely by Grofé) or the Concerto. The influence of 1920s jazz is clearly audible, but the most prominent element is the variety of orchestral moods he projects and the ingenious ways he achieves them. The standard orchestra is augmented by saxophones, a huge array of percussion, and—one of Gershwin’s most prized souvenirs from his 1928 trip to Paris—a set of four French taxi-horns.

The Planets—the best known or orchestral work by Gustav Holst—is based upon the astrological personalities of the planets.

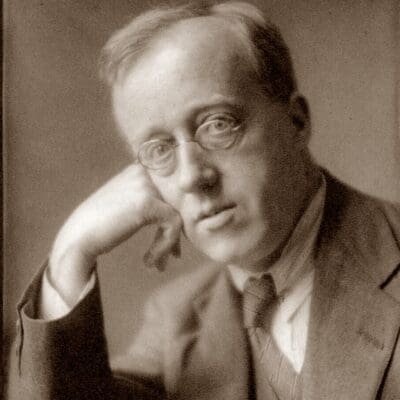

Gustav Holst (1874-1934)

The Planets, Suite for Large Orchestra, Op.32 – Mars, Venus, Mercury, and Jupiter

“There is nothing in the planets (my planets, I mean) that can be expressed in words.”

– Holst, to conductor Adrian Boult

When Holst began composing the music of The Planets in 1914, he was nearly 40 years old. He had been an eclectic sampler of Eastern philosophies and mysticism since he was a young man, and this work came out of a brief flirtation with astrology. Holst, however, never seems really to have believed in astrology—he used it only as source of musical inspiration. He wrote in 1913 that “I only study things that suggest music to me. Recently the character of each planet has suggested lots to me, and I have been studying astrology fairly closely.” As Holst suggested, the movements of The Planets are based upon the personalities attributed to the seven astrological planets: Mars being “headstrong and forceful,” Neptune “subtle and mysterious,” and so forth.

Holst completed the work in 1917. The music of The Planets is more massive and somewhat more radical than anything Holst ever wrote. The work uses a vastly expanded orchestra, augmented by such exotic timbres as bass oboe and bass flute. Holst, who spent much of his youth as a trombonist in several bands, lavished a great deal of forceful and difficult music on a large brass section that includes six horns, four trumpets, three trombones, tuba and that most beloved of all British band instruments, the euphonium. His score also calls for a large percussion battery (at least seven players), two harps, celesta, and in the final movement, organ and an offstage women’s chorus. Holst’s acquaintances must have been surprised at the formidable and occasionally violent nature of this piece—the 5/4 rhythm and crashing dissonances of Mars must have seemed particularly shocking coming from this mild-mannered and unfailingly gentle man. Despite its massive nature, The Planets also shows elements of his earlier style, which blended elements of Oriental and north African music, and Eastern mysticism, with the foursquare and solid harmony of English church music.

Early audiences assumed that the first movement, Mars, the Bringer of War, was written in response to the first world war. In reality, Holst completed this movement before the outbreak of hostilities and probably had Mars’s astrological significance in mind rather than current events. However, this movement still manages to convey a sense of Europe’s inexorable slide towards a senseless conflict. Holst sets up a savage 5/4 rhythm in the opening bars that underlies the whole movement. An ominously rising theme is passed from bassoons and horns to the trombones, and eventually to the entire brass section. As the volume builds, Holst introduces a sliding countermelody. The euphonium and trumpets introduce a contrasting idea and an accompanying fanfare. The movement continues as a development of these paired themes, building towards a crashing conclusion.

Nothing could be more of a contrast to Mars than the calmly flowing Venus, the Bringer of Peace. Holst sets aside the trumpets, trombones, and drums of the opening movement to focus on the more delicate colors of harps, woodwinds, and strings. The solo horn plays an upward-flowing melody, which is answered by descending woodwinds. A contrasting, but equally placid melody is introduced by solo violin. This is no sharply textured Botticelli Venus, but an impressionist portrait in soft, watercolor textures.

Mercury, the Winged Messenger opens with a feeling of perpetual motion, passing brief bits of melody from instrument to instrument. The orchestration is extremely light, focusing on the woodwinds and giving prominent passages to the celesta. A central episode uses an exotic melody first heard in the solo violin and then repeated several times throughout the orchestra. Holst’s daughter notes that the inspiration for this passage came from folk musicians that he had heard on a trip to Algeria. In its final section, Mercury returns to the nimble character of its beginning.

For Jupiter, Holst returns to full orchestra, but this movement contains none of the threatening darkness of Mars—Holst described Jupiter as “…one of those jolly fat people who enjoy life.” The main theme is a rollicking syncopated melody first heard in the horns. The first contrasting section turns to a slightly slower triple meter melody, again introduced by the horns. After a brief return to the opening texture, there is a second triple meter theme; a broad hymn-like melody marked Andante maestoso. (A few years later, Holst did, in fact, use this melody to set a patriotic hymn.) To close off the rondo form, Holst includes a final statement of the main theme.

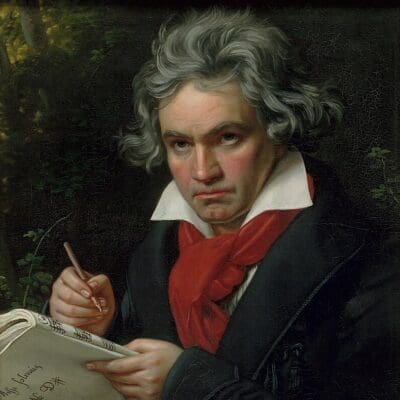

Beethoven’s ninth symphony ends with an enormous choral finale, setting the ecstatic words of Fredrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 – Choral Finale

Almost a quarter of a century separates Beethoven’s first and ninth symphonies, a quarter century that saw encroaching and eventually total deafness, personal tragedies, musical triumphs, and the composition of Beethoven’s greatest music. When compared to the abstract works that Beethoven wrote at the end of his life, the Symphony No. 9 seems a bit dated. There are many elements that seem to hearken back to the “heroic” style that had occupied him in the opening decade of the 19th century. Much more striking, however, are the new and innovative elements: the extraordinary introduction to the opening movement, the masterful contrapuntal writing, and of course the massive finale—the first symphonic movement to include vocal soloists and a chorus. The essential plan of the ninth symphony—a four-movement work in D minor with a choral finale—seems to have been complete by 1818, but then Beethoven set the symphony aside for a few years. He began serious work in the summer of 1823, completing the Symphony No.9 in February of 1824.

The symphony was not an immediate success, and several reviewers wondered openly whether Beethoven’s age and deafness might be beginning to take their toll. Part of their reaction may have been the result of a poor performance. The musicians hired for the Akademie concert on May 7, 1824 had had only three rehearsals and it is obvious that they did not have the new symphony under their fingers at time of the premiere. Beethoven himself did little to help the performance: he insisted on conducting, even though he was completely deaf by this time. Even the most sympathetic observers noted that his wild gestures were completely out of sync with the orchestra. The performance was saved from utter disaster by an assistant conductor, Ignaz Umlauf, and the orchestra’s concertmaster.

Beethoven seems to have been fascinated for many years with Schiller’s poem An die Freude (“To Joy”—written in 1785). The poet and playwright Friedrich Schiller was one of the leading voices of democratic thought in Vienna, and his is plays were occasionally banned during the 1790s because of their “dangerous” sentiments. Beethoven may have thought about setting An die Freude as early as 1796 and may in fact have composed a now-lost setting of the poem in 1798 or 1799. Lines from An die Freude appear even earlier, in a cantata Beethoven composed on the death of Emperor Leopold II in 1790, and selections from the poem also appear in his opera Fidelio (1806). In setting An die Freude in the ninth, Beethoven freely rearranged and edited Schiller’s poem, focusing in particular on the lines that deal with the winged goddess Joy, and the feelings of brotherhood she inspires. The unforgettable melody used to set Schiller’s poem had a similarly long history. Some scholars have traced the “Joy” melody to as early in Beethoven’s career as 1794, in his Choral Fantasy (1808) and his song Kleine Blumen, kleine Blätter (1810). where it reached its nearly final form

The enormous and complex finale begins with crashing dissonance: Richard Wagner referred to these measures as the “fanfare of terror.” He hints at the “Joy” theme before presenting it in full in the low strings—one of the most satisfying and profound moments in all of music. (This is exactly where our performance starts.). After three variations on the “Joy” theme, the “Fanfare of terror” returns. Beethoven’s masterstroke, used to introduce the voices, is a brief text of his own (“O friends, not these tones…”) that he inserts before beginning An die Freude. In a few short measures, this recitative changes the character of the symphony—rejecting the storm and stress of the previous music and setting the finale onto a joyful course. After the first set of choral variations, Beethoven inserts a droll “Turkish March” that serves as the background to a tenor solo and gradually develops into an orchestral double fugue. One more triumphant statement of the “Joy” theme, and then another startling innovation: a thundering recitative for the full chorus, doubled by trombones. There is an extended moment of hushed awe that gives way to a second and even more magnificent double fugue for chorus and orchestra. The coda is full of irresistible joy: fast-paced orchestral passages alternating with sublime vocal lines.

program notes ©2025 by J. Michael Allsen

To view current and past program notes, please visit Michael Allsen’s website.