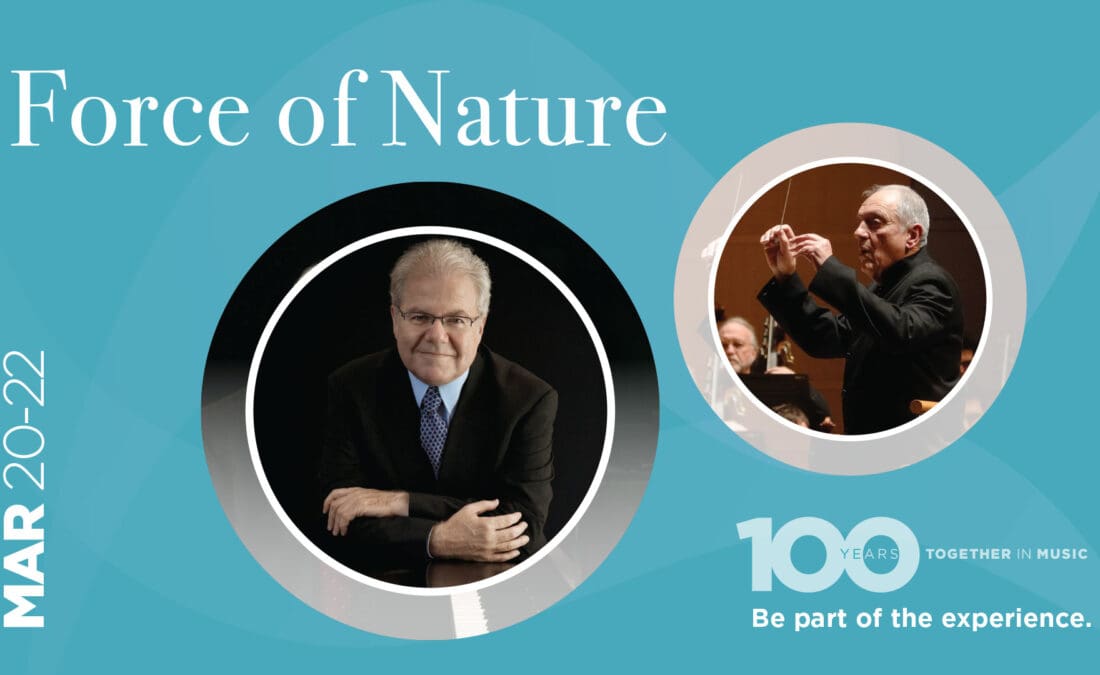

We invite you to read through Michael Allsen’s program notes for the March 20th-22nd performance of Force of Nature.

Program Notes

This program opens with one of Strauss’s great programmatic symphonic poems, Till Eulenspeigel’s Merry Pranks. This tells the story of the outrageous Till—represented by an equally outrageous solo horn motive—and his exploits, done in a spirit of good fun—a spirit that endures even after his execution at the hands of officials who have no sense of humor. We then welcome an old friend, pianist Emanuel Ax, to perform the largest and grandest of Mozart concertos, the Piano Concerto No. 25. Mr. Ax has performed five times previously with the MSO: in 1979 (Chopin, Piano Concerto No. 1), 2005 (Brahms, Piano Concerto No. 2), 2008 (Chopin, Piano Concerto No. 2), 2016 (Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 4), and 2018 (Brahms, Piano Concerto No. 2). Grammy winning composer Gabriela Ortiz grew up steeped in the indigenous music of her native Mexico: her parents were members of Los Folkloristas, a famous folk group dedicated to performing music from around Latin America. Her Téenek channels the spirit of the Huasteca region of Mexico. We close with another great programmatic work, Respighi’s Pines of Rome, which opens with a scene of children at play, and ends with a stirring depiction of a Roman Army on the march.

This lighthearted piece is one of the early symphonic poems with which Strauss established his international reputation as a young composer.

Richard Strauss

Born: June 11, 1864, Munich, Germany.

Died: September 8, 1949, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany.

Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche, Op.28 (Till Eulenspeigel’s Merry Pranks)

- Composed: 1894-1895.

- Premiere: November 5, 1895, in Cologne.

- Previous MSO Performance: 1946, 1962, 1970, 1984, and 2010.

- Duration: 16:00.

Background

A symphonic poem takes its inspiration and musical form from a story, a visual image, a poem, or some other non-musical source. In this case it is the story from German folklore of a mischievous rascal.

After Franz Liszt established the symphonic poem (or tone poem) as a form in the 1850s, many Romantic composers took on this genre. The finest of all late Romantic symphonic poems, however, are seven works that Richard Strauss completed when he was a young man, from Macbeth (1888) though Ein Heldenleben (1898). Each of these works explores in vivid programmatic detail the life of a single character, whether a hero or—as in Till Eulenspeigel (1895)—an anti-hero. Strauss often denied that his symphonic poems were dependent on programs, and should stand on their own as purely musical works, but this statement was seemingly obligatory among late Romantic composers. However, he also boasted at one point that: “I want to be able to depict in music a glass of beer so accurately that every listener can tell whether it is a Pilsner or a Kulmbacher!”

In the case of Till Eulenspiegel, the central character is a German folk-hero who may have been based on a 14th-century German peasant famed for his wisecracks and outrageous practical jokes. Till made his first appearance in a 1511 Schwankbuch (a collection of humorous stories), and Till Eulenspiegel stories were a staple of German folklore. The word Eulenspiegel means “owl-mirror,” probably a reference to an old German proverb which translates roughly as: “One recognizes his own faults as dimly as an owl recognizes his own reflection in a mirror.” Strauss’s choice of Till as character may have had something to do the brutal criticism of his 1894 opera Guntram. A character who thumbed his nose at the forces of orthodoxy and tradition, even after he was lynched, must have been attractive to a young composer who felt wronged by the establishment.

What You’ll Hear

Is relatively easy to follow the character of Till, personified by an exuberant theme for solo horn, as he causes havoc, and is eventually put to death…though his mischievous spirit returns in the end!

The complete title of the work is Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks, Based Upon the Old Rogue’s Tale, set for Large Orchestra in Rondo Form. Though this is far from a classical rondo, the famous theme at the opening does return at several points. This theme, beloved (or feared) by every orchestral hornist, may well have been borrowed from the composer’s father, Franz Strauss, one of the finest hornists of the 19th century. One well-known story is that the tune was a standard part of the elder Strauss’s daily warm-up routine, adapted here two characterize the mischievous Till. Strauss was at first reluctant to provide a written program, but some years later, he relented and provided the following outline of the action:

Merry Till cavorts through life, his jaunty progress charted at first by a carefree tune for solo horn. The anti-hero enjoys poking fun at mankind’s pretensions, religious hypocrisy and the world of academia; he disrupts a village market, unsuccessfully attempts to find true love, impersonates a priest, and continues whistling on his way. An ear-splitting roll on the side-drum signals that Till must answer for his “crimes.” He is brought before judge and jury yet is unwilling to observe the trial in silence until the death sentence is announced. Trumpets and drums herald Till’s journey to the scaffold, where his merry pranks are ended.

With this description in hand, Till Eulenspiegel works wonderfully as a picturesque programmatic piece. The ending is particularly effective, with the part of Till given to a shrill E-flat clarinet, making fun of the stern pronouncements of the trombones and low strings. When the moment of execution arrives, the trombones and tuba deliver the fatal blow, and Till’s spirit rises to heaven. There is a solemn epilogue on the opening music, but even this is not to be taken too seriously, as Till gets in the last word.

This work, like the majority of his 27 piano concertos, was composed for one of Mozart’s public concerts in Vienna.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria.

Died: December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria.

Piano Concerto No. 25 in C Major, K. 503

- Composed: Between late 1784 and December 4, 1786.

- Premiere: In Vienna on December 5, 1786, with Mozart as soloist and conductor.

- Previous MSO Performances: 1984 (Garrick Ohlsson) and 1997 (Ignat Solzhenitsyn).

- Duration: 32:00.

Background

Contrary to the usual view of Mozart as a spontaneous genius, this concerto was the result of two years of tinkering. It was apparently one of Mozart’s own favorites.

Mozart settled in Vienna in 1781, and his reputation and success in his early years there came largely through his performances at the homes of aristocratic patrons, and public “subscription” performances of his own works. His piano concertos were all written for this venue. Viennese audiences demanded new concertos at every concert, and Mozart responded with an amazing series of fifteen concertos written during his first five years in Vienna. The last of these, the Piano Concerto No. 25 of 1786, was apparently a personal favorite of Mozart’s, and he performed it several times over the next few years.

The traditional view of Mozart is that he was a spontaneous genius—that brilliant works sprang fully-formed from his head. Mozart certainly had phenomenal creative powers. We have descriptions, at least from Mozart himself, of feats like composing a minuet in his head while he was writing a letter. However, Mozart was also a skillful craftsman, and many of his works were the result of a careful process of experimentation, editing and revision. The Piano Concerto No. 25 was one of these. Between the time he began the concerto in 1784, and the time he finished it in 1786 (about 24 hours before the first public performance), he made two substantial sets of revisions. Several critical sections, including the first solo entrance, were rewritten entirely. But if you’re tempted think any less of Mozart for being less than perfect on the first pass, remember that during the two years this concerto was on the back burner, he completed over forty other works, including two operas!

What You’ll Hear

The concerto is in three movements:

• A large opening movement in sonata form contains a couple of unusual features.

• A lyrical Andante.

• A brilliant rondo finale.

The Piano Concerto No. 25 is one of Mozart’s largest piano concertos, and a wonderful example of his mature musical style. The first movement (Allegro maestoso) begins conventionally enough, with an orchestral passage that establishes the key and lays out most of the thematic material. The piano enters, at first hesitantly, but then with more confidence, with a solo introduction. This passage maneuvers the orchestra into re-introducing the main theme, a dotted figure. After a transitional section, the piano, supported by the strings, introduces the flowing second theme. The movement continues in a traditional sonata form, but during the piano cadenza, Mozart adds an orchestral background, a very unusual feature among concertos in this period. This cadenza leads to a final coda.

As in most Mozart concertos, the second movement is a lyrical slow movement (Andante). The orchestra introduces a gentle theme with support from the piano. When the piano takes up this theme, it is expanded and decorated. There is a brief note of tension in the middle of the movement, but the music soon glides into a final statement of the theme by the piano. A short coda brings the Andante to a close and sets up the final movement (Allegro). This is set in rondo form, based on a reoccurring dancelike theme heard first in the violins, that alternates with contrasting ideas. In this movement, the focus is almost entirely on the soloist, and the Allegro contains some of the flashiest solo passages of the concerto.

This rhythmically intense work deals with transcending what the composer calls “artificial borders”—political, racial, cultural, and artistic.

Gabriela Ortiz

Born: December 20, 1964, Mexico City, Mexico.

Téenek – Invenciones de Territorio

- Composed: 2017

- Premiere: October 12, 2017, by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Gustavo Dudamel conducting.

- Previous MSO Performance: This is our first performance of the work.

- Duration: 12:00.

Background

Gabriela Ortiz is among Mexico’s leading composers. She started by playing in her parents’ folk group, where she absorbed styles from all around Latin America.

Gabriela Ortiz came by her interest in folk music quite naturally: her parents were founders of the famed group Los Folkloristas, a group dedicated to performing both Mexican music and vernacular styles from throughout Latin America. Even as she was playing charango and guitar in her parents’ group, she was also studying classical piano. After initial studies in composition in Mexico, with Daniel Catán, and others, she earned masters and doctoral degree in composition in London. Today she is among Mexico’s most prominent composers. Ortiz, who was recently the composer-in-residence at Carnegie Hall, has a particularly close relationship with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and its music director, Venezuelan Gustavo Dudamel; their album Revolución diamantina, featuring three of her works, won three Grammy awards in 2025. The LA Phil and Dudamel commissioned and gave the world premiere of her Téenek – Invenciones de Territorio of in 2017.

What You’ll Hear

This work is a series of varying “inventions” of differing style and texture.

Alejandro Escuer provided the following explanation of Ortiz’s Téenek – Invenciones de Territorio for the world premiere by the LA Philharmonic in 2017:

Téenek is the language spoken in the Huasteca region, which encompasses the states of Veracruz, Tamaulipas, San Luis Potosí, Hidalgo, Puebla, and Querétaro in Mexico. Its name means “local man,” in reference to all the men and women who belong to a place whose mere existence determines their destinations in time and space: their territories. Indeed, in any region of the world, human beings from any given era determine a way of BEING that transcends time and defines their relationship with their surroundings, no matter what their race, skin color, political borders, or socio-economic condition may be. We are all mortals, just as our domains, differences, borders, and possessions will eventually disappear, if not in decades, over the course of centuries. In the end, human beings transcend such conditions and circumstances by simply BEING, by culturally existing, by everything that remains.

Téenek is a sonorous metaphor of our transcendence, a strength that alludes to a future where there are no borders, but rather, a recognition of the actual particularities and differences between us that propitiate our development while at the same time enriching and uplifting us.

Music thus bears witness to a gradual history of matches and mismatches, of ancient cultures and new symbols, of wayviolis to resist and comprehend the world by imagining sounds and senses, of that vital rhythm that lends meaning to the sense of belonging, and of roots that identify us culturally. Through the plain and simple idea of fitting in, of not dividing but, rather, recognizing otherness, Téenek reflects on the importance of reaffirming identities through fragment

It is precisely because of this that Téenek is composed of a series of apparently dissimilar inventions which find their strength in their differences, enrichment, and musical development: these are interwoven and transformed over time in a discourse that demonstrates how the existence of borders may be diluted in pursuit of the powerful idea that our potential future lies in recognizing our differences.

Téenek opens with a brisk dancelike section that replicates the combination of triple and duple meters heard in the son huasteca, one of several Mexican regional folk styles. This gives way to a rather mysterious interlude and another section of almost frantic rhythm. Another quiet interlude includes features for solo English horn and violin above an atmospheric percussion background. A solo marimba leads into the final section which closes with an almost savage reprise of the opening rhythm.

Respighi, the leading Italian composer of instrumental works in the early 20th century, was an acknowledged master of orchestration.

Ottorino Respighi

Born: July 9, 1879, Bologna, Italy.

Died: April 18, 1936, Rome, Italy.

The Pines of Rome

- Composed: 1923-44.

- Premiere: December 14, 1924, in Rome, by the Augusteo Orchestra, under Bernardino Molinari.

- Previous MSO Performance: We have performed this work seven times previously at these concerts between 1956 and 2015.

- Duration: 21:00.

Background

Respighi’s best-known works are a trio of symphonic poems that provide vivid sound portraits of his beloved Rome, where he lived for most of his career.

Ottorino Respighi was the leading Italian composer of concert music in his day and he was certainly one of the 20th century’s great masters of orchestration—the skillful use of the huge palette of tone colors available in a symphony orchestra. He wrote some adventurous works, but Respighi was no modernist: in fact he much more often turned to music of the distant past. Sometimes he created an imagined past, as in the mighty “pseudo-Roman” music at end the of his Pines of Rome, an imaginative picture of an ancient Roman army on the march. He also adapted older music directly, as in his three sets of Ancient Airs and Dances, which draw on 16th- and 17th-century music for the lute. The “Roman trilogy” of Respighi includes three large multi-movement symphonic poems that are easily his most famous works: The Fountains of Rome (1916), The Pines of Rome (1924), and Roman Festivals (1928). In these works, the composer creates a sonic portrait of his native Rome. From Fountains, celebrating the great Bernini monuments, to the wild revelry of Festivals, Respighi paints a colorful, programmatic picture of the Eternal City. For the central work, The Pines of Rome, Respighi uses images of the ancient trees that line Rome’s parks and promenades to inspire four programmatic episodes. The four sections are played without pauses.

What You’ll Hear

This work includes four vibrantly drawn programmatic scenes: of children at play, a funeral procession in the catacombs, delicate night music and the song of a nightingale, and finally, of a Roman army on the march.

In the score, Respighi provides the following description of the first section, Pines of the Villa Borghese: “Children are at play in the pine grove of the Villa Borghese, dancing ‘Ring around the Rosy;’ they mimic marching soldiers and battles; they chirp with excitement like swallows at evening, and they swarm away.” The music is appropriately light and high-spirited, with quick woodwind and horn lines beneath trumpet fanfares.

For Pines near a Catacomb, he turns to a much darker, “quasi-Medieval” texture. Respighi was fond of using Gregorian chant or chantlike themes in his orchestral works, and the Lento second movement begins with a quiet melody that builds gradually towards a tremendous orchestral statement near the end of the movement. Here are “the shadows of the pines that crown the entrance to a catacomb. From the depths rises a dolorous chant which spreads solemnly, like a hymn, and then mysteriously dies away.”

In his description of Pines of the Janiculum, the composer notes: “There is a tremor in the air. The pines of the Janiculum hill are profiled in the full moon. A nightingale sings.” This is profoundly calm and quiet night-music, carried by the softer voices of the orchestra throughout. At the very conclusion, a recording of a nightingale’s singing is added to the orchestral texture—one of the very earliest instances of a composer using prerecorded sounds in a concert piece.

The final section is titled Pines of the Appian Way. Respighi gives the following colorful description of an ancient Roman army on the march: “Misty Dawn on the Appian Way. Solitary pines stand guard over the tragic countryside. The faint unceasing rhythm of numberless steps. A vision of ancient glories appears to the poet; trumpets blare and a consular army erupts in the brilliance of the newly risen sun—towards the Sacred Way, mounting to a triumph on the Capitoline Hill.” The movement opens quietly, with a slow and inexorable march, but builds gradually towards an enormous brassy peak. To create this picture of Roman military might, Respighi’s score calls for six bucinae—Roman war trumpets. (He also provides the helpful suggestion that modern trumpets may be used if bucinae are not available!)

program notes ©2025 by J. Michael Allsen

To view current and past program notes, please visit Michael Allsen’s website.