At the National Opera Association’s 2023 Conference in Houston, Music Director John DeMain led a masterclass for five opera students and was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award — the NOA’s highest honor! He joins a list of highly-esteemed award recipients, including Marilyn Horne, Beverly Sills, and Dominick Argento. Recipients are selected by the NOA’s Board of Directors on the basis of the following criteria:

- Substantial international and national operatic career

- Previous awards and/or recognition at the national or international level

- Significant number of years in the profession

- Attractive “name recognition” for the conference

- Demonstrated commitment or interest in fostering operatic/musical education

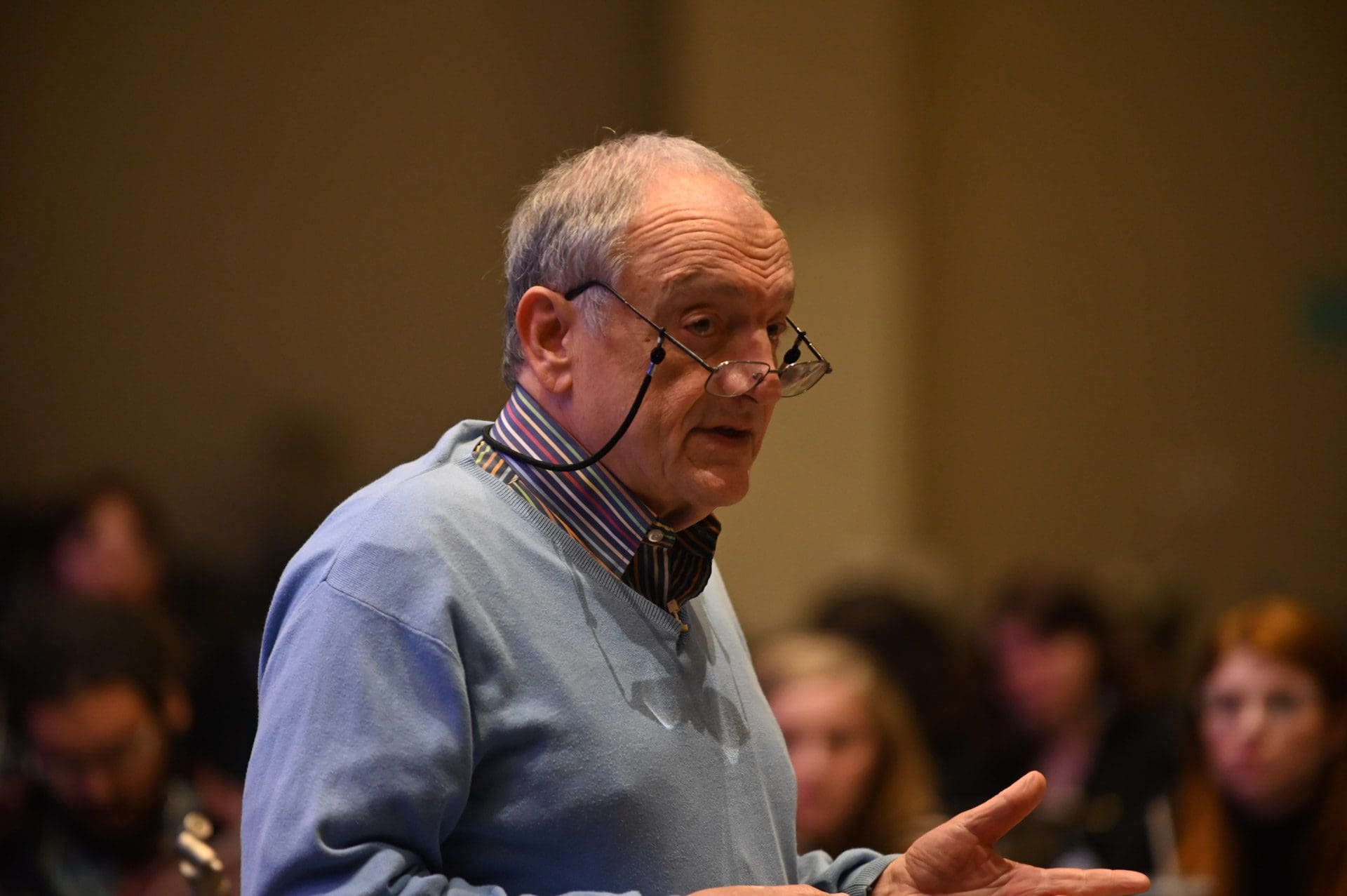

Please join us in extending our gratitude to the NOA and celebrating this huge honor for John! Photos from the masterclass and closing banquet, plus his acceptance speech, are below. Thank you to Kirk Severtson for providing all images below!

Masterclass — Friday, Jan. 6

Closing Banquet — Saturday, Jan. 7

John DeMain’s Lifetime Achievement Award Acceptance Speech

National Opera Association Conference Closing Banquet

January 7, 2023

Houston, Texas

Thank you, Lisa. Well, I must say, when Kirk called to tell me that the NOA wanted to give me their Lifetime Achievement Award, I was truly taken aback. My first response was that I was the right age. He then told me he liked the fact that I was still active. So do I. I’m celebrating my 29th season with the opera and symphony in Madison, WI. And I have finished putting the finishing touches for my 30th anniversary season. Living and working all these years in Madison, I often wondered if people remembered any of the projects I had been associated with over my long career. I am truly honored and deeply moved that NOA remembers. I am also thrilled to have members of my family here tonight.

I have been fortunate my entire adult life to go from one project to the next, with barely any time to bask in any successes, and really happy I didn’t have much time to think about the failures. Preparing for this award caused me to pause and look back, and remember. Remember the people who took a chance on me when I was so very young and inexperienced. My life and love affair with opera began with the Met broadcasts every Saturday on the radio. At the age of nine I sang the role of Amahl in Amahl and the Night Visitors with the Youngstown Symphony, and Youngstown Playhouse. I had a fabulous boy soprano voice with easy high C’s and a natural vibrato. And then, at the age of 13 my voice changed, and as the great summer theater producer John Kenley said to me: ”You have the loudest, ugliest voice for an Italian that I’ve ever heard.” I said: “Why do you think I’m conducting?” So I began playing the piano as a teenager for my voice teacher’s talented students.

My love for theater resulted in a long association with the Youngstown Playhouse where in my high school years I conducted and appeared in musicals and plays. At Juilliard I played voice lessons for almost everyone on the vocal faculty, and in the summers I worked in summer stock theaters conducting Broadway musicals featuring some of the biggest stars of Broadway and television at that time. A particular highlight among many was the chance to conduct the legendary Ethel Merman in Call Me Madam. I coached and played auditions for many of the cast members during the winter months in New York. Though I was a piano major at Juilliard, I loved conducting and longed to get into opera. When the new Juilliard at Lincoln Center opened in 1969, at an alumni concert with Leontyne Price, the esteemed director Rhoda Levine, whom I had worked with at Juilliard in extra curricular opera projects, came up to me at intermission and asked if I had any interest in opera. I said yes and that started the ball rolling.

My first professional position was with the National Educational Television Opera Project, which led to being the 2nd recipient of the Julius Rudel Award at New York City Opera, after that a couple years with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, and suddenly I found myself in this great city that we are convening in at this moment. I was recruited to become the first music director of the newly-created Texas Opera Theater, designed to bring opera to small communities where opera was seldom or never performed. During a hiatus in the tour in the winter of 1976, I learned that Houston Grand Opera (HGO) was going to produce Porgy and Bess. I stormed into the brilliant and innovative general director David Gockley’s office and told him that he should hire me to conduct it. He hired me and the rest was history.

The goal of that production was to open up the piece to more stage directors, restore all the recitatives and cast really fine singers in the small roles so one could relish in the beauty of a fully-sung opera, and lastly, to present as authentically as possible the Black experience and culture that would make the cast members proud to be in the piece. I was 32 years of age when we debuted our game-changing production of Porgy and Bess. My dream of conducting that opera suddenly became a reality.

The success of Porgy had a profound effect on HGO and myself as well, having won the Grammy, the Tony, and the Grand Prix du Disque for the recording of this milestone production. This led to my eventual appointment as music director of HGO. This for me was the beginning of a kind of “Our Future Together” moment. David Gockley believed that an opera company was a music theater production company and that all forms of music and musical theater were under its purview. This led to new editions of Baroque operas, operas by Rossini, the first production of Sweeney Todd in an opera house, and the second one of Hal Prince’s Candide. The Houston Opera Studio for young artists was established along with an opera theater workshop to work on new operas. And at the top of the list was the creation of major new operas. I was on the podium conducting world premieres of works by Carlisle Floyd, Leonard Bernstein, John Adams, and Phillip Glass to name a few. The level of creativity was astounding and exhilarating as HGO was creating the blueprint for a model American opera company. During that time I spent ten years as music director of Opera Omaha and, together with Steven Wadsworth, created the Fall Festival, devoted to new works, and operatic rarities.

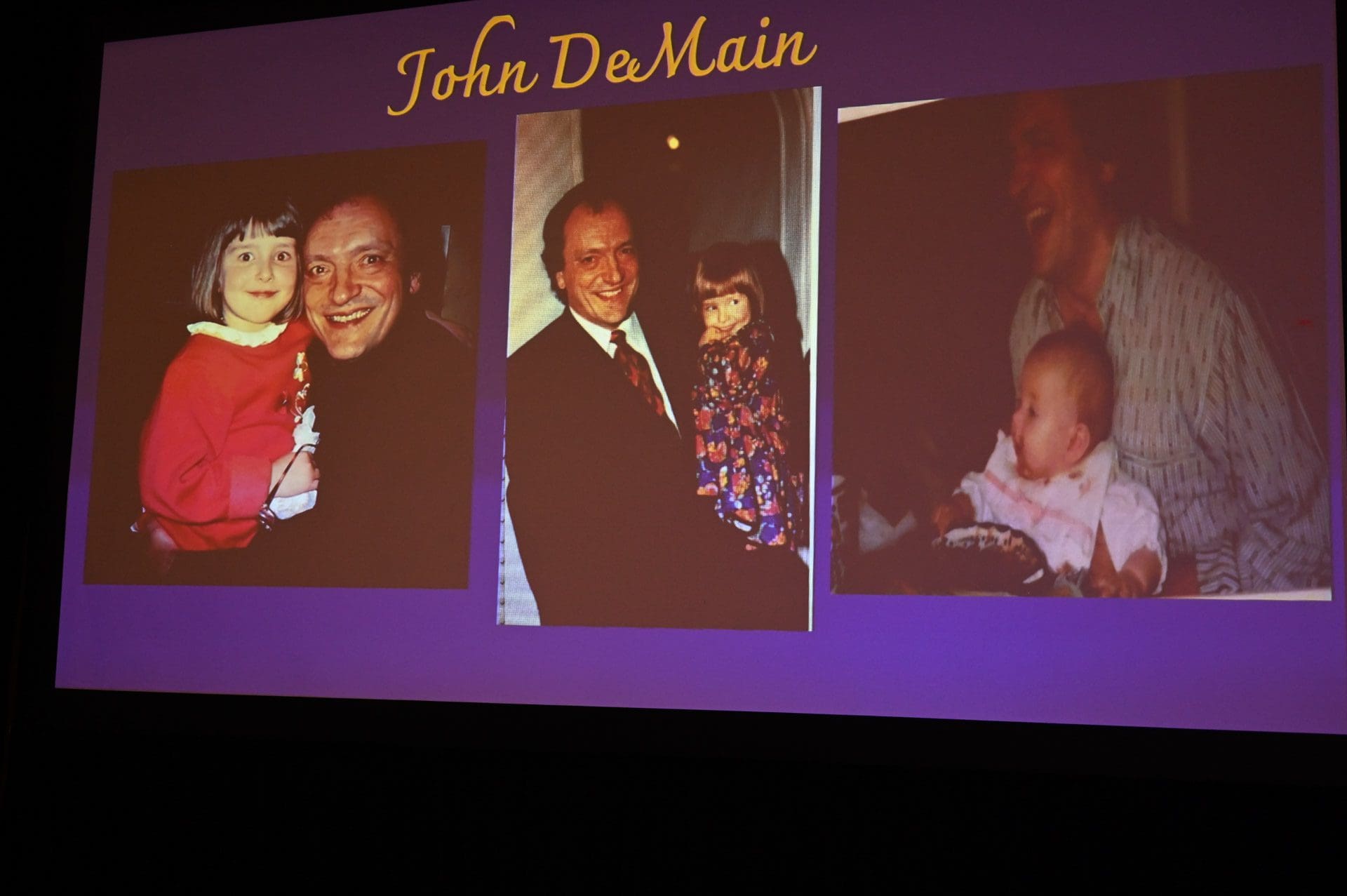

I always wanted to have my own symphony orchestra, not an easy feat to come by when your career is so steeped in opera, but Madison Symphony Orchestra which, at the time also included Madison Opera, looked at my resume because I was in opera. In 1994 with my wife Barbara, who passed away 3 years ago, and our 2-year-old daughter Jennifer who is here tonight, we began our journey to Madison. During these years with the orchestra and opera, I was able to spend 10 years at Opera Pacific as artistic director, and a lot of guest conducting all over the US as well as abroad. When I saw the roster of names of past winners of this prestigious award, I was impressed at the scope and spectrum of awardees, from superstar singers to those of us who work at every level in our field. And the invaluable work that our educators in this room do every day in a class room or a university production. In addition to the big houses I worked in, I loved my time at Lake George, Chautauqua, Aspen, Wolftrap, Glimmerglass, and of course my beautiful Madison.

Today, in Madison, we are adapting to the challenges and opportunities facing our performing arts organizations. Everything we do at the opera and symphony is informed at the start by our deep commitment to equity, diversity, and inclusion. And in my role as a conductor, I have tried my whole career to make it about the music, not about personalities. It’s about the work, and so many of you in this room are about the same task: the joyous work of carrying on an art form that we care deeply about. For me, opera is the Olympics of singing, and the pursuit and discovery of great voices, technically secure with personalities that make the music jump off the page, is my passion. I also am committed to being involved with productions where the stage direction is not at odds with what’s coming out of the pit, but rather deeply integrated so that the musical and dramatic arc soars, and the audience is the winner. I have been blessed to work with great opera orchestras including the Madison Symphony, who realize the special nature of playing opera. And I am deeply grateful to the great and knowledgeable coaches who have made me look good all these years. Opera is a collaborative art form, and I think of myself as a collaborative artist. When I’m in a rehearsal room, I’m home. But most importantly, I have had for over 50 years the best seat in the house on the conductors podium where I could relish in the glories of the human voice, working with countless artists, some of whom are in the room tonight. That one should have such access to great singing has truly been one of my life’s greatest joys.

These past few days I have been able to be in the room with those of you who work in the educational arm of our industry. It is you who set the stage for the special talents to emerge from the class room to the professional world. It is you who will provide the coming generations with the tools that they will need to move forward into our future together. Our art form doesn’t really have to worry about our product becoming obsolete. Great art transcends the ages, but we do have to worry about how it is experienced in this technological age. Giant screens in our living rooms bring everything in closeup, and our overly-large theaters can present problems for the new generations weened on the Jumbotron. I don’t have any easy answers, but I have learned to embrace smaller chamber-like operas in smaller non-traditional spaces where the audience can be close to the performers and experience their acting as well as vocal prowess in a way that is rather unique from what is the norm. I encourage you to consider this if you are not already doing so. I have heard discussions about expanding the pedagogy of singing to include more contemporary styles of singing. Opera singers can sing musical theater repertoire, and we at the audition table want to hear this music as we produce all kinds of music theater works. I want to encourage composers when they write about contemporary subjects to think a la Stephen Sondheim to write for different kinds of voice types, vocal style and vocal production, and not be stuck in a 19th century style of singing that may not relate to the audience or the subject matter you’re writing about. So many new operas are being written with beautiful vocal lines and not sing songs obligatos as was too often the case in the recent past. Composers must never forget that in opera, it’s about the singers on the stage. They must have the most interesting aspect of the music. I always like to say that opera is your life sung back at you.

So let’s put our collective lives and our stories on the stage and sing our hearts out. If we do, I don’t think we’ll have to worry about the future of this great art form. To all of you in this room, I say again, your work is essential. Without you, there can be no us. I salute you, and I thank you for honoring me. Thank you for this, NOA, and thank you family and friends for your great support. Tonight you have brought me great joy.