Thank you to the Wisconsin State Journal for the insightful story sharing highlights from our Music Director John DeMain’s career and your Madison Symphony Orchestra’s 100th Anniversary Season that begins in September 2025. Enjoy!

——————————————————————————————

3 Decades of Steady, Unforgettable Growth

Longtime leader’s final season with the baton coincides with MSO’s centenary

John DeMain’s tenure to culminate in epic season for Madison Symphony Orchestra

Shun Graves, Wisconsin State Journal, Jul 24, 2025

He had arrived in Madison with an operatic background and an international pedigree.

Yet ahead of his 1993 guest program — effectively his tryout for the Madison Symphony Orchestra’s top job — John DeMain implored his future musicians with one simple request: “Don’t forget me.”

His utterance stuck with musicians like longtime percussionist Rick Morgan. Here was the Houston Grand Opera’s music director, the conductor who’d premiered works by era-defining composers like Leonard Bernstein and raised his baton on five continents, seeking the approval of the orchestra and audiences in Madison.

They didn’t forget, not then and certainly not today.

For here was the man who would transform the MSO into a professional organization, an orchestra that could finally tackle the toughest music and make it more accessible to all.

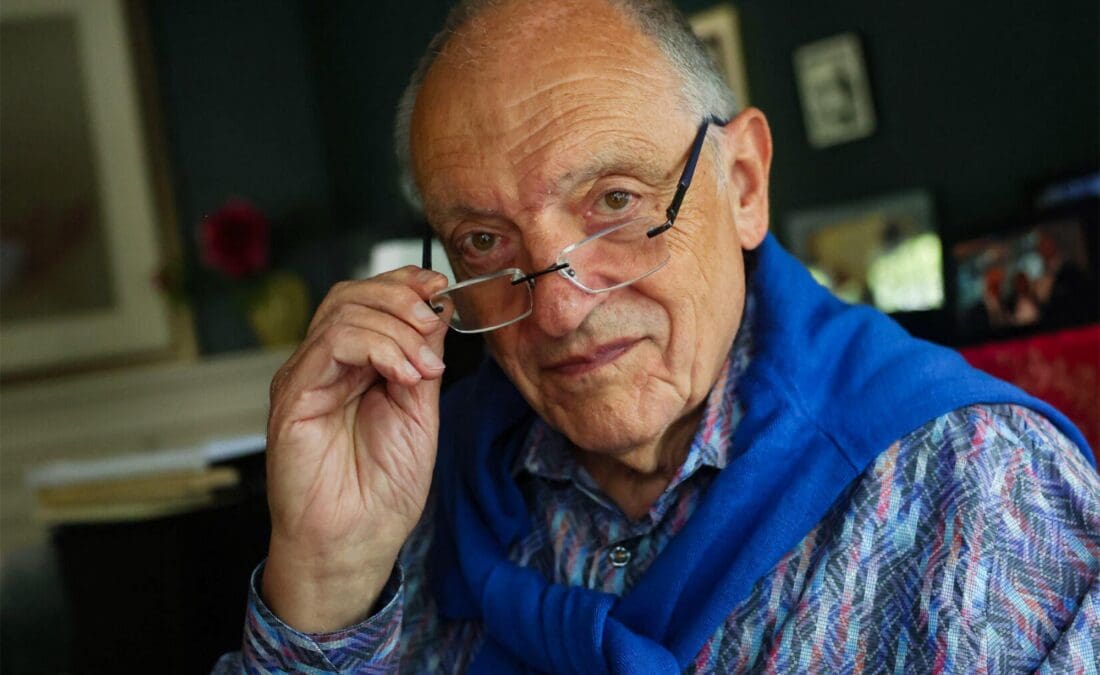

“My ambition was to not baby this orchestra at all,” said DeMain, 81, perched on a couch at his Madison home as he reflected on his tenure, which began after his selection in 1994.

As DeMain prepares for his final season as the MSO’s music director, he’ll leave behind an orchestra whose talent didn’t just explode under his baton; it required a new home.

DeMain’s last season will also mark the MSO’s centennial.

You can’t separate the two. The triumphant final concert, a free, two-day series at the Overture Center next June, will wrap up the orchestra’s first 100 years by showcasing just about everything DeMain worked to achieve.

Back in 1993, when he emerged as one of three finalists after a global search for the orchestra’s next music director, DeMain first had some personal goals.

He’d mostly conducted orchestras that accompanied operas, and he found classical music conductors in the U.S. were often pigeonholed into either opera or purely symphonic work.

“So when I came to hear this orchestra, I thought, I would like to have my own symphony orchestra,” he said.

DeMain would hear some problems too.

As he prepared for that guest program in October 1993, DeMain appraised the winds and brass sections of the orchestra as “terrific.” The strings, not so much.

The string section’s small size and out-of-tune playing hamstrung the MSO’s version of Richard Wagner’s “Tannhäuser” overture during DeMain’s 1993 guest performance. But his bid didn’t end there, because the rest of the program stunned.

Michael Allsen, who writes program notes and serves as the MSO’s de facto historian, played in the brass section until 2018. He remembered performing during DeMain’s guest concert with astonishment, especially during his rendition of Dimitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5.

“It was just tremendously exciting,” Allsen said.

One other candidate mounted a solid guest performance but dropped out. The field narrowed to two finalists.

In February 1994, not long after the other candidate’s guest performance, DeMain secured the gig to succeed Roland Johnson. After his selection, DeMain told the Wisconsin State Journal he would keep the “existing audience on the edge of their seats.”

But change took time.

Some of the problems DeMain identified early on stemmed from how the MSO had evolved since its first season, 1926-27. The first three directors had established the orchestra as a Madison cultural institution, but it lacked the standards of many professional orchestras.

Case in point: the lack of blind auditions.

Most professional organizations try out prospective musicians by listening to them behind a curtain. Madison’s orchestra didn’t do that, resulting in a “closed shop” culture, he said.

Many of the MSO musicians taught at the University of Wisconsin, he said, and would often pick from their students to fill out their respective sections in the orchestra.

“We started auditioning behind a screen,” DeMain said. “I made sure that we had a chance to discuss the musicians together, the candidates, and we would make unanimous choices. And gradually we got better and better and better people in the orchestra.”

As the orchestra started to attract musicians from places like Milwaukee and Chicago, DeMain also got the OK to expand the string section.

That would help ameliorate some of the problems there. His other solution? Rehearsing music slowly and improving intonation, note by note, an intensive but ultimately fruitful method that would help DeMain achieve some of his higher-flying goals.

The DeMain method

He calls it “having integrity with the music.”

To become familiar with a symphony, DeMain sits down at his piano and works through the orchestral score, which shows all the different instrumental sections. He marks it up. Green for woodwinds and red for brass, for example.

And he listens.

“When I listen to a recording, I like to find performers and conductors who are actually doing what the music says,” DeMain said, “trying to find a way to really do what the music is suggesting and says, and doesn’t have a personal interpretation on it that is so distorting that it’s an ego thing, that it’s not trying to really do what the composer wanted to do.”

Take a symphony by Gustav Mahler. DeMain can tell within 20 measures — maybe a minute — of a recording whether the conductor followed the music or not.

If Mahler says to speed up imperceptibly from one point to another, then do it. Don’t change the tempo somewhere else. Definitely don’t make what DeMain decries as “willful” changes to what Mahler spelled out.

You can’t achieve such small-scale intricacies without a top-notch orchestra.

Morgan, the percussionist, remembers how DeMain’s understanding of the music shined when he visited Madison in 1993. In the following years Morgan would learn that to accomplish his musical vision, DeMain had a “forceful” approach and presence, though he would also joke around.

That rapport with the musicians, while also pushing them toward what Allsen calls “the next level,” would prove pivotal to DeMain’s longevity as he pushed a number of other changes.

He compressed rehearsals into the week ahead of a concert. And the number of concerts multiplied. DeMain pushed the MSO to add a Sunday matinee performance after its traditional Saturday evening showing. Eventually the orchestra would add a Friday show too.

The changes accompanied, and sometimes coalesced into, the ultimate challenge for the musicians: taking on the most technically complicated but widely known symphonies.

In his opening concert as the MSO’s music director in September 1994, DeMain tackled Mahler’s first symphony in a performance described by the State Journal as “gutsy” but with “shakiness” in some sections. He would go on to conduct the rest of Mahler’s symphonies, compositions considered to rank among the greatest orchestral music.

“Repertoire like that also creates orchestras,” Allsen said. “It stretches the orchestra, challenges the orchestra.”

But one challenge didn’t emanate from the stage.

New venue another legacy

When DeMain joined the MSO, the orchestra performed at a theater that once screened silent movies.

The Capitol Theater, then known as the Oscar Mayer Theater, hosted the MSO and several other performing arts groups. The orchestra sounded great from the mezzanine, DeMain said, but beneath the balcony it sounded completely different.

“It sounded like the Salvation Army on a bad night,” he said. “It was horrific sitting under there.”

Thus began his push to find a new home for the MSO. He considered the Orpheum Theater but found it had similar acoustic challenges. That meant a completely new venue was in order.

Then came Jerry Frautschi, who with his wife, American Girl founder Pleasant Rowland, spearheaded the creation of a new arts center for Madison, ultimately dedicating $205 million toward the project.

The Overture Center for the Arts opened in 2004, and “it changed our lives,” DeMain said.

Now the performing arts center will serve as center stage for DeMain’s valedictory season.

Guest conductors make debut

The MSO’s centennial will open Sept. 19 with an all-Tchaikovsky program. Season highlights include “Cirque de la Symphonie,” a circus show accompanied by the MSO the next night, and programs featuring well-known artists like cellist Alban Gerhardt, pianist Yefim Bronfman, violinist Rachel Barton Pine and the Los Angeles Guitar Quartet.

The four programs each featuring one of those artists will also offer a glimpse into the MSO’s next 100 years.

Robert Reed, the MSO’s executive director and a member of the committee searching for DeMain’s successor, said the orchestra has reviewed hundreds of conductors.

Last year, the orchestra brought three guest conductors to Madison. Four more will show their chops this season as they accompany those guest artists.

Robert Moody leads the Memphis Symphony Orchestra in Tennessee, among other groups. Kazem Abdullah conducts around the world and previously directed the Sinfonieorchester Aachen in Germany.

Tania Miller directs the Brott Music Festival in Canada. And Laura Jackson has served as the longtime music director of the Reno Philharmonic Orchestra in Nevada.

All told, the selection process seems more dynamic than in 1993, when the MSO presented three distinct candidates.

DeMain, meanwhile, plans to attend a rehearsal led by each guest conductor, but he won’t attend the concerts.

“Because I don’t want people coming up to me and saying,

‘What’d you think? What’d you think? What’d you think?’” he said. “I’m not supposed to think on those issues. But what I’ve heard is that the level of conductor is very high, and the orchestra is playing really well for them. They’re showing off for each other.”

He’s excited to see how the choice of a successor is made, as he’s decided not to have a hand in it. Plus, he has a whole season to prepare for.

‘Community Gift and Dream’

The MSO bills its 100th season’s final concert as the “Community Gift and Dream”: a two-day festival in June 2026. Admission will be free.

Aside from serving as a gift to the city, the concerts will deliver on another of DeMain’s goals, a challenge faced by classical music everywhere: bringing in new, younger audiences.

It’s a future that DeMain sometimes ruminates about. How about adding a visual aspect to the performance? Video close-ups of the musicians, perhaps?

“I don’t think we should be running a Coca-Cola commercial while we’re playing a Beethoven symphony,” he said. “I think it should help expand our senses for that particular moment.”

For now, though, the baton remains the focus for DeMain.

He’s not in the market for another directorship, he joked, but he plans to keep conducting, perhaps as a guest, perhaps with a fancy title like emeritus.

“I don’t know how long I’m going to hold up,” DeMain said. “As long as I can hear, see, and the arms go up and down, then I’ll work when asked.” “Repertoire like that also creates orchestras. It stretches the orchestra, challenges the orchestra.”

When John DeMain arrived in Madison as one of three candidates vying to lead the Madison Symphony Orchestra in 1993, he exhorted the musicians not to forget him. After more than three decades, DeMain will enter his final season as music director as perhaps the MSO‘s most memorable figure.