We invite you to read through Michael Allsen’s program notes for the October 14, 15 and 16 performance of Sublime Violin & Journeys below.

Program Notes

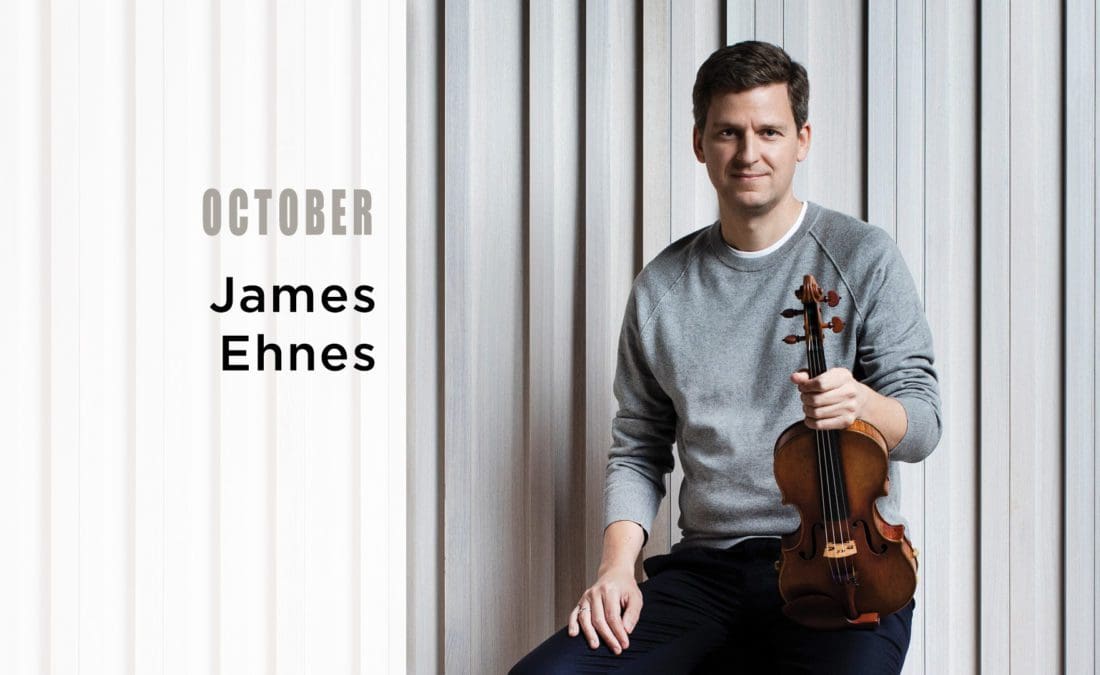

Our second program opens with Death and Transfiguration, Richard Strauss’s profound musical meditation on the end of life…and what comes after. We are proud to welcome back audience favorite James Ehnes for these concerts. He previously appeared with the Madison Symphony Orchestra in 2012 (Bartók, Violin Concerto No.2), 2015 (Bruch, Scottish Fantasy), and 2019 (Brahms, Violin Concerto). Here Mr. Ehnes plays one of the finest American works for violin, the Barber Violin Concerto. We close with Mendelssohn’s third symphony, inspired by the composer’s tour of Scotland when he was a young man.

One of Strauss’s great series of symphonic poems, Death and Transfiguration deals with the themes of death following a life of earthly struggles, and the soul’s transfiguration into a triumphant afterlife. Strauss lays this out quite clearly is a series of masterfully-scored musical episodes

Richard Strauss

Born: June 11, 1864, Munich, Bavaria (Germany)

Died: September 8, 1949, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, West Germany

Death and Transfiguration, Op. 24

- Composed: 1888-1889.

- Premiere: Strauss conducted the first performance in Eisenach, Germany on June 21, 1890.

- Previous MSO Performances: 1939, 1966, 1977, and 2009.

- Duration: 23:00.

Background

Strauss asked his friend Alexander Ritter to write a poem describing the program be published with the score of this work, but Strauss himself later described its concept more concisely in a letter.

Strauss’s most frequently-performed works are a series of symphonic poems (or tone poems) he composed as a relatively young man. This most Romantic of orchestral forms is an expression of poetic or philosophical ideas in music, or frequently, pure program music: telling a story or painting a scene. Strauss’s tone poems adapt his own dramatic interests and frankly autobiographical details into his distinctive and freely-developing musical style. They are also masterpieces of orchestration, making colorful use of large orchestral forces. He wrote his first four tone poems, Aus Italien (from Italy), Macbeth, Don Juan and Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration) in quick succession between 1886 and 1889. While the first three are relatively straightforward pieces of program music, Death and Transfiguration was more metaphysical, based upon a conception of Strauss’s own, rather than a literary work. His friend Alexander Ritter later wrote a poem outlining the work’s conception (appended to the published score), and Strauss himself outlined the concept in a letter in 1894:

“It was six years ago that it occurred to me to present in the form of a tone poem the dying hours of a man who had striven towards the highest idealistic aims, maybe indeed those of an artist. The sick man lies in bed, asleep, with heavy irregular breathing; friendly dreams conjure a smile on the features of the deeply suffering man; he wakes up; he is once more racked with horrible agonies; his limbs shake with fever—as the attack passes and the pains leave off, his thoughts wander through his past life; his childhood passes before him, the time of his youth with its strivings and passions and then, as the pains already begin to return, there appears to him the fruit of his life’s path, the conception, the ideal which he has sought to realize, to present artistically, but which he has not been able to complete, since it is not for man to be able to accomplish such things. The hour of death approaches, the soul leaves the body in order to find gloriously achieved in everlasting space those things which could not be fulfilled here below.”

A strikingly similar conception appears in his friend Gustav Mahler’s second symphony, written at virtually the same time, and Strauss was also deeply influenced by Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, which he had heard for the first time shortly before beginning Death and Transfiguration. (He had spent the summer of 1888 working as a vocal coach for a production of Tristan at the Bayreuth Festival.)

What You’ll Hear

The opening section reflects the dying man’s struggles against death, culminating a grand brass “transfiguration” theme. Following his remembrances of his life, death finally takes him, and the final section portrays victory and peace.

Death and Transfiguration is in several sections, clearly outlining Strauss’s picture of the dying artist. The irregular rhythms of the opening clearly show the dying man’s halting breaths—probably inspired by the music that accompanies the dying Tristan in Act III of Tristan und Isolde. He rouses himself to remember his childhood, in the guise of a lovely series of woodwind and violin solos above luminous horns and strings. But pain intrudes again and a strident strike from the timpani announces a tumultuous battle scene as he fights for life. In Ritter’s poem: “But Death grants him little sleep or time for dreams. He shakes his prey brutally to begin the battle afresh. The drive to live, the might of Death. What a terrifying contest!” At this end of this battle, the brass briefly announce a triumphant theme that will represent his eventual transfiguration and the realization of his ideals.

Exhausted but wakeful after this battle, the artist’s life passes before his mind’s eye: a series of struggles and triumphs that is the longest section of Death and Transfiguration. The transfiguration theme rings out throughout, but in the end he once more subsides, with weakening heartbeats portrayed by the timpani. Death finally triumphs with an angry proclamation from the brass—what Ritter called “the final iron hammer-blow.” What follows is Strauss’s evocation of “everlasting space”—shimmering chords which build gradually to a full statement of the transfiguration theme, first in lush strings and then triumphantly in the full orchestra. The work closes in a mood of quiet exaltation.

Epilogue

Nearly 60 years later, in 1948, Strauss completed his final work, the Four Last Songs—written at a time when he and his wife were in declining health, and he was clearly aware of his own approaching death. The last and longest of these, Im Abendrot (In Twilight) has an elderly couple looking out over a darkening valley that represents their waning lives. When the soprano finally sings of death itself, the mood is not of resignation or fear, but of calm acceptance and satisfaction. In the closing bars, Strauss includes a quiet reference to Death and Transfiguration’s main theme: identifying himself with the dying hero of the symphonic poem and bringing his career as a composer to a symbolic end. When he was on his deathbed in 1949, he remarked to his daughter-in-law: “It’s a funny thing, Alice. Dying is exactly as I composed it sixty years ago in Death and Transfiguration.”

Among the finest American concertos of the 20th century, Barber’s 1939 Violin Concerto embraces both lush romanticism and more aggressive modernist style

Samuel Barber

Born: March 9, 1900, West Chester, Pennsylvania

Died: January 2, 1981, New York City, New York

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op.14

- Composed: 1939-1940.

- Premiere: The public premiere was played on February 7, 1941 in Philadelphia, by the Philadephia Orchestra, with violinist Albert Spalding

- Previous MSO Performances: 1994 (Benny Kim), 2005 (Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg), and 2011 (Robert McDuffie).

- Duration: 25:00.

Background

This work was originally commissioned for violinist Iso Bruselli, though Briselli eventually declined to premiere the work.

In May 1939, Barber received a commission for a violin concerto from the American soap magnate Samuel Fels, on behalf of the Ukrainian violinist Iso Briselli. Briselli had come to the United States in 1924 as a 12-year-old prodigy studying with Carl Flesch at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music. Fels later served as a guardian and patron to the young violinist. (Briselli, in turn, would later administer the Fels philanthropic foundation.) At the time, Barber was living in a small Swiss village, where he completed the first two movements of the concerto. When war broke out in Europe, Barber returned to Philadelphia to take a teaching post at the Curtis Institute, and he submitted the first two movements to Briselli. There is a well-known—and incorrect—story about the concerto’s history from this point onwards. According to this version of events, Briselli complained that these movements were not quite the technical showpiece that he had in mind, and when Barber obliged with the brilliant third movement, the violinist returned it as “unplayable.” The third movement was vindicated when a young violin student named Herbert Baumel played it for a committee of Curtis teachers after working for only a few hours on the challenging solo part.

Later biographers Barbara Heyman and George Diehl reconstructed the events somewhat differently. Briselli, it seems, was in fact quite enthusiastic about the first two movements. The controversy over the last movement was not about “playability,” but about its extreme contrast with the first two movements: an almost frantic Presto that seemed at odds with the lyricism that preceded it. He suggested revisions to the form that would bring it into more traditional lines, but Barber refused. Eventually the commission was withdrawn, and Barber retained his rights to the concerto. There was a private performance by the Curtis Orchestra, with Baumel as soloist. After a few minor revisions, Barber offered the concerto to violinist Albert Spalding, who premiered it in Philadelphia in early 1941.

What You’ll Hear

The concerto opens with two relatively lyrical movements, while the third is aggressive and spiky.

The opening movement (Allegro molto moderato) begins with a broad and lyrical theme laid out by the solo violin and strings. The movement continues as a rather gentle dialogue between soloist and orchestra, moving towards a grand romantic pinnacle near the end, but coming to a rather quiet conclusion. This understated tone continues in the second movement (Andante sostenuto), which begins with a long, songlike melody presented by the solo oboe. When the solo part enters, it presents a somewhat more impassioned melody, before picking up the oboe’s theme. Once again, the movement moves towards a climactic moment near the end, only to close quietly.

Several of Barber’s biographers have pointed to the Violin Concerto as a turning point in his career: as the work in which he turned away from the essentially romantic style of his early music towards a more austere style. The third movement was composed some months after the Allegro and Andante—after his return from Europe—and there is certainly a distinct difference between the mild quality of the two opening movements, and the hard-edged finale. The last movement, marked Presto in moto perpetuo, begins with the soloist moving at a furious pace, above oddly-placed accents in the orchestra. The violin passes the baton to the woodwinds near the middle of this movement, only to pick it up again, at the same pace, after a brief rest. The motion of this movement stops only at the very end, just before one final burst of solo fireworks.

As a young man, Mendelssohn was able to tour Europe, and became a kind of musical sponge: absorbing musical and other influences everywhere he went. His famous “Scottish” symphony was directly inspired by a visit to Scotland in 1829.

Felix Mendelssohn

Born: February 3, 1809, Hamburg, Germany

Died: November 4, 1847, Leipzig, Germany

Symphony No. 3 in A minor Op. 56 (“Scottish”)

- Composed: Though he did initial sketches for the symphony in Scotland in 1829, most of it was composed in 1840-1842 while he was in Berlin.

- Premiere: Mendelssohn led the first performance in the Leipzig Gewandhaus on March 3, 1842.

- Previous MSO Performances: 1945, 1964, 1982, and 2004.

- Duration: 40:00.

Background

The landscape, history, and culture of Scotland fascinated 19th-century Romantics in all of the arts: from the phenomenally popular novels of Sir Walter Scott, the poetry of Robert Burns, and landscape paintings by Alexander Nasmyth and Jacob More to the first truly “romantic” ballet, La Syphide. Mendelssohn was only one of many 19th-century composers to be inspired by Scotland.

As the son of a wealthy German family, Mendelssohn was able to indulge in the “grand tour”—years of wandering Europe during his young adulthood. This was no idle tourism, however: he intended to refine his skills, and to pick up musical influences from across the Continent. Well-known as a musical Wunderkind, he presented concerts, and wrote music where ever he went. He met a particularly enthusiastic reception when he arrived in London in the spring of 1829, presenting concerts of his own works, and appearing as a piano soloist. That summer, he and a friend left for an extended tour of Scotland. Mendelssohn was deeply affected by this visit, sketching landscapes, writing enthusiastically to family and friends, and in a couple of cases, finding inspiration for musical works: the concert overture The Hebrides and his fine “Scottish” symphony.

That he found Scotland so attractive is hardly surprising: the Romantics loved Scotland, and Mendelssohn’s letters are filled with appreciative descriptions of what he saw and experienced.. Soon after arriving in Edinburgh, Mendelssohn visited Holyrood Abbey. He wrote to his parents that: “The chapel beside it has now lost its roof, it is overgrown with grass and ivy, and at the broken altar Mary was crowned Queen of Scotland. Everything is ruined, decayed, and open to the sky. I believe I have found there today the beginning of my Scottish Symphony.” Apparently that same day, he sketched out the opening theme of the Andante introduction. The work was largely set aside for more than a dozen years, however. It was not until late 1840, while Mendelssohn was engaged as a conductor in Berlin, that he began serious work on the symphony. He worked on it through most of the next year, finishing it in time for its premiere in Leipzig in the spring of 1842. This was to be his last completed symphony, and many agree that is also his finest.

What You’ll Hear

The symphony, which has a few distinctly “Scottish” touches, is set in four movements:

- A turbulent opening movement with a slow introductory idea. Both of the main themes are derived from this introduction.

- A lively scherzo, with a dancelike main theme.

- An alternately serene and forceful slow movement.

- A warlike finale that ends with a rousing coda.

Mendelssohn was clearly uncomfortable about writing a symphony that could be understood as purely programmatic” but a few musical elements of the symphony would clearly have been recognized as distinctly “Scottish” in character: the “Scotch snap” (a reverse dotted rhythm), the occasional use of bagpipe-style drones, and the clarinet’s folk-dance melody at the beginning of the second movement. As a whole, however the symphony works perfectly in purely musical terms: most of the musical material grows organically from the opening motive. He also specified that the movements were to be played without pauses.

The first movement begins solemnly (Andante con moto), with the theme Mendelssohn sketched out in 1829. This introduction leads almost seamlessly into the main body of the movement (Allegro un poco agitato). Both main themes are derived from Mendelssohn’s 1829 idea: a restless melody introduced by the low strings and flutes, and an almost hesitant closing theme played by the violins. The development focuses on the main Allegro theme, working it out in an intensely contrapuntal manner. The recapitulation is conventional enough, but the end is a surprise: after a sudden storm, the movement rather suddenly dies away, and there is a reminiscence of the opening bars before it moves directly into to the scherzo.

The scherzo (Vivace non troppo) opens with a playful dance theme introduced by the clarinet. In place of the usual contrasting trio, there is a rather agitated development section that again fades suddenly to provide a transition to the next movement. The Adagio’s main idea is a lovely long-breathed melody spun out by the strings. This sublime mood alternates with uneasy march-like music from the brasses and woodwinds.

The beginning of the fourth movement is the only abrupt transition in this symphony. Though the opening of this movement is marked Allegro vivacissimo in the score, Mendelssohn suggested in his preface that this might be described in the program as Allegro guerriero—a “warlike Allegro.” Warlike associations are there to be sure: an insistent pulsing background, and an almost angry theme. A more peaceable contrasting idea bears a clear family resemblance to the first movement’s main theme. This idea is quickly swept away by more intense music several times, until it finally wins out in a long duet for clarinet and bassoon. This introduces the final section (Allegro maestoso assai), where low strings introduce a broad theme. This is quickly taken up by the full orchestra to bring the symphony to a stirring conclusion.

________

program notes ©2022 by J. Michael Allsen

To view current and past program notes, please visit Michael Allsen’s website.